EDITORIAL 3

EDITORIAL 3Political Progress

Wilderness at the Front Line

National Parks Journal, JUNE 1999 Vol 43 No 3

EDITORIAL 3

EDITORIAL 3

Political

Progress

Wilderness

at the Front Line

NPA MATTERS 4

Memories

of "Our Henry"

NPA in Costa

Rica

Towarri National Park 7 by John Macris

ENVIRONMENT NEWS & ACTION 9

Earth

Garden & the Giant

Timbarra

win & loss

Help for

Hexham Swamp

News from the

NPWS

FEATURES

National park estate expansion 11 by Paul Barnes

Extinction & its prevention:

BioDiversity 13 by Andreas Glanznig

Extinction

& conservation 14

by JR Giles

Honeybees

& biodiversity 17

by Kristi MacDonald

Conservation

of species 18

by Ian M Johnstone

Getting

involved in marine protection 21 by

Craig Bohm

ACTIVITIES PROGRAM (Supplement following p 12)

REVIEWS 23

FRONT COVER: Towarri

National Park, Liverpool Range, NSW

Photo: John Macris

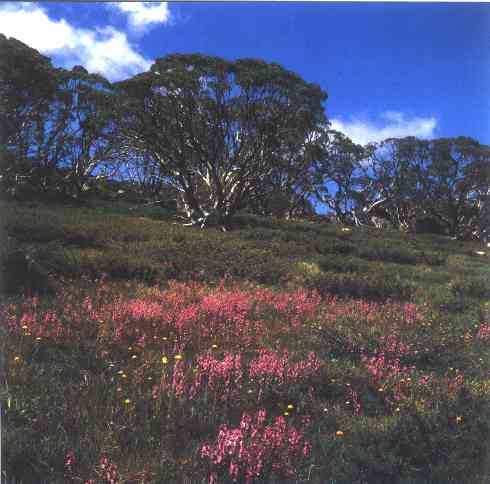

BACK COVER: Alpine Meadows

ABOUT THE NATIONAL PARKS JOURNAL

Progress in NSW

The results of the State election bring stability to government in NSW. The ALP has won a clear majority in the Legislative Assembly. In the Legislative Council it does not have an absolute majority but, as the cross bench now has a majority of conservation-minded MPs, the Government now has less need to compromise on environmental matters. We shall be hoping that the second Carr Government does not waste this opportunity to govern effectively for the environmental benefit of us all.

Mr Bob Debus is the new Minister for the Environment. He was instrumental in the recent addition of the Canyon Colliery site, at the head of the Grose Wilderness, to the Blue Mountains National Park. He supported this despite a vociferous campaign against him, in the midst of the NSW election, by the high-profile Dr John Wamsley. We look forward to working with Mr Debus - we don’t expect agreement on every issue, but are pleased that such a knowledgeable and experienced Minister has been appointed. There are some clear priorities for nature conservation in NSW and we hope to work with the Minister and the Government on these, particularly:

In this issue Paul Barnes catalogues seventeen of the larger areas of forest recently added to the national parks estate in the north-east. The cooler winter months are a good time to visit to enjoy them and to see why they were worth preserving.

Tom Fink

NPA President

Wilderness at the Frontline

"Wilderness - we call it home " is the message over a colourful picture of an aboriginal man carrying spears and throwing stick, surrounded by little boys.

This is the cover page of a glossy brochure which then goes on to state: "The means by which indigenous people use and manage their country has changed. Today they use vehicles to access their cultural sites and firearms with which to hunt. To insist that indigenous use of wilderness places be restricted to traditional practices is to treat their cultures as museum pieces, denying their evolution."

The brochure identifies hunting and the construction of houses in wilderness as key issues for aboriginal communities.

However, it fails to outline the likely real impacts that would accompany such use, including firearms, access roads, dams, power lines, garbage tips and sewage plants.

It is simply cant to rationalise the use of intrusive modern technology by some aboriginal people in wilderness areas on the basis that it is a natural development of traditional ways, when it is utterly alien to the original cultural perspective.

So, it may come as a surprise to learn that the Australian Heritage Commission, a hitherto pro-wilderness and pro-conservation agency, has put out this brochure.

The brochure has resulted from a very restricted, if not stacked, consultation begun several years ago by the AHC, pressed on it by aboriginal rights activists in some environment groups and the bureaucracy. The consultation was unrepresentative and culminated in a little-known meeting in Western Australia in May 1998, attended by just 25 people. Official records of that meeting clearly show the subordination of wilderness protection and nature conservation to a supposed "aboriginal right".

The AHC goes on to unilaterally redefine wilderness in a triumph of political correctness. The AHC uses more words to outline the supposed aboriginal perspective than to describe wilderness.

The AHC’s propositions have more relevance in western and northern Australia, where large areas of remote wild land are owned by aboriginal people with a continuity of occupation, language and culture. How they use this land is a matter for their decision within the framework of laws designed to protect threatened species.

The situation in national parks and dedicated conservation areas is another matter altogether. It is and must be a matter of broad public ownership and debate. This is particularly so in NSW and other eastern states with specific legislation (such as the NSW Wilderness Act) designed to protect wilderness and keep it from the degrading influences of modern technology regardless of race or creed. Public concern for wilderness has seen more than 1.5 million ha in NSW and another million ha in Victoria protected as national parks - some of our most precious natural areas, giant old growth forests, rugged, sweeping sections of the Great Dividing Range, hidden rainforests. These areas would otherwise have been left to the mercy of the loggers, miners and redneck vandals.

The AHC is mistaken to adopt the narrow and divisive agenda of a few ideologues who wrongly see wilderness as an impediment to land rights and Aboriginal sovereignty. This brochure is the tip of an iceberg aimed at crippling wilderness conservation, or at the least pressuring governments to link aboriginal ownership and privileged use with further conservation reserves, no matter how tenuous the current aboriginal associations.

This agenda has surfaced clearly in the just-released NSW NPWS’s public assessment report for the proposed Grose Wilderness in the nominated Blue Mountains World Heritage Area. Here, at pages 12-13, is an explicit statement that "indigenous Australians are fundamentally opposed to the concept of wilderness." Such a sweeping statement might be appropriate as a personal submission in response to the report; it is totally inappropriate in a report by a public agency charged with the protection of wilderness.

There is evidence that the anti-wilderness view is not shared by many ordinary aboriginal Australians. Last year when I visited Mutawintji National Park, the first aboriginal-owned park in NSW, I was interested to hear quietly from some that the present substantial wilderness zone in the park should not be abolished or watered down - they like it just the way it is.

The AHC brochure uses a respected aboriginal Australian, Pat Dodson, to talk of finding common ground, of reconciliation, of sitting down in the bush to understand one another. Sadly, this publication amounts to an attempt to bushwhack the concept of wilderness protection and represents division, not reconciliation.

NPA strongly supports reconciliation with aboriginal people and their involvement with management of wilderness and the national parks estate. Australia is proud of its tolerance and accommodation of diverse views. Wilderness is the only land category which uncompromisingly protects nature and supports evolution free of human hands. True reconciliation should support wilderness, not seek its annihilation.

Noel

Plumb

Executive Officer

NPA Matters

NPA in Costa Rica

Cath Webb, Western Project Officer, represented NPA and World Wide Fund for Nature at a wetlands conference held in San Jose, Costa Rica, from 10-18 May. The international meeting of signatories to the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands was attended by representatives from government as well as from non-government organisations.

A conference is held every three years to review progress on the aims of the Convention and to discuss future imperatives for worldwide wetlands conservation. Cath's main objective in Costa Rica was to canvass opinion on the recent listing and Memorandum of Understanding for the Gwydir wetlands (see April NPJ), as well as seeking opportunities for similar decisions elsewhere in Australia. The Gwydir MoU was the first such private agreement in Australia, so there are no precedents here for implementation of this kind of multiple-use management.

Cath will report in the next Journal on progress at the conference.

Memories of "Our Henry"

Ladders: this was the mundane title of a magazine article that first led me into the innovative mind of Henry Fairlie-Cuninghame.

It was the mid-fifties and we were both immersed in the exploration of limestone caves.

Henry had been an early member of Sydney University Speleological Society and had taken part in many of their discovery trips. His expertise was the design, improvement and construction of specialised equipment for this new sport of speleology.

His article in the SUSS Journal had the flavour of a minor thesis. He critically reviewed every ladder then available and explained in great detail the methodology behind his design and how he went about manufacturing his ladder. I faithfully followed his instructions and during the latter part of 1958 I produced two elegant cave ladders that remain a testimony to Henry's ingenuity.

During this period Henry also developed new lighting techniques for the photographic recording of the vast underground chambers being discovered.

A profile of Henry in the 1953 SUSS Journal states that he "was President for the years 1952 and 1953.

He graduated in Physics and Maths in 1952 and is now working with STC at Liverpool. His activities as a photographer have gained him prizes in several NSS (USA) competitions with his best work coming from Croecus and other Tasmanian caves." Henry was twenty-three at the time. His photographs also appeared in Walkabout Magazine and The Australian Encyclopaedia.

Four years later his eight-page article entitled Inflating balloons with hydrogen in caves appeared in the SUSS Journal. In this article he said that he was prompted to investigate the topic after witnessing unsuccessful attempts to inflate balloons during the 1957 Nullarbor expedition. The article described his experiments with four options. It rated the options in order of merit and costed the balloons, with prices ranging from four pence halfpenny to eight pence. He recommended cotton instead of the usual string to measure roof heights as it was both lighter and did not stretch as much.

The balloon article was probably Henry's last foray with speleology. In recent times I found him reluctant to talk about this era, but I guess that this is not surprising because Henry's interest was always in the present. Towards the end of the fifties he made the switch to the world of bushwalking and continued to embrace it with passion for the rest of his life.

It was not until 1964 that I finally met the man behind all those magazine articles. The old NPA tour bus was in trouble on the rough access road down to Yalwal. It was my first trip with NPA and the last year for the bus. Henry was the driver and trip leader. The front axle had come adrift from the spring mounting and dangerously affected the steering. With the aid of my car and Henry's resourcefulness we managed to tow the axle back into place, and a jubilant group set off on a well-planned and successful trip of discovery.

The hallmark of Henry's trips was the planning. He often spent hours studying aerial stereo photos to obtain as complete a picture as possible of a new area. Pre-trip promotion in the Journal ran to many pages with an outline of the topography and the geology of the area to be visited and details of transport arrangements, and meeting places as well as each day's planned activity and proposed camp site. This was backed up with a comprehensive reference list of books and maps. It was all aimed at firing the interest of members.

The sixties was an action-packed decade for Henry. There were so many places to explore, to wonder at and just to enjoy. He was ever-mindful of the need to interpret the areas visited and to assess the potential for the greater scheme of national parks for the future.

His regular, enthusiastic Journal reports of places visited could cover four to five informative pages and his ongoing contribution to the Explorer group, and later the Reserves Committee, added more important and factual material for the assessment of national park values.

Henry's dedication to NPA was total. In fact it was his life at that time, just as a decade earlier he had been totally absorbed by speleology. As well as leading trips away, he played an active role in the production of the Journal and totally managed the activities program. At one time he even had his aged father, Sir Alan, helping with the wrapping and mailing of the Journal. Henry attended every meeting and often enhanced these with the showing of his slides. These were always detail-perfect, whether landscape or nature in close focus.

Henry's diligent scientific research skills came to the fore during the Myall Lakes campaign. He produced a seminal document describing the rutile industry: this was an important tool in the long struggle to gain national park status for this area.

During the turbulent years when the Association was closely involved in the enabling of the National Parks Act, Henry served as Central Region Vice-President and in following years served as a member of State Council.

The Muogamarra Volunteer Bush Fire Brigade involved Henry for many years, in the fighting of fires and analysing fire-fighting practices. He produced follow-up reports - a particularly critical one following the major Warrumbungle fire of November 1967 but, as always, this report had positive ideas for improve ment.

His fascination with the wonders of the Australian bush never left him time to think about himself and how he felt, particularly if he was leading a trip. The word "tired" was not in his vocabulary. It is hard to remember Henry ever expressing discomfort on a bushwalk. Consideration of the discomfort of others was not a strong point, but generally did not matter because his pervading positive joviality prevailed during times of adversity.

Days on tour were packed with interest. There was no time to stand around talking.

In those days Henry could talk and walk at the same time. In more recent years, on bushwalks you could look forward to a pleasant stop when Henry decided to elaborate on a topic. Henry loved to talk.

He could elaborate on any subject and give a well balanced opinion. His scientific explanations of the physical world were presented in a way which rivalled Professor Sumner Miller. He enjoyed an audience, and if he strayed from his topic he could arrest attention with "The point is this ..." and off he would go, standing beside the campfire, tall frame hunched, hands be hind his back, explaining the universe in a deep penetrating voice. He was a staunch defender of the campfire as an indispensable part of bushwalking culture.

Somehow, Henry's voice was so penetrating that he could not whisper. His first quiet words of the morning would resonate across the camp and further sleep was impossible. He was always first up and ready to embrace the day, often with an exuberant, comic remark.

At base camps his car horn would blast, accompanied by his version of "In the morn you will hear a Horn".

He also had the ability to back his arguments, particu larly scientific ones, with a vast amount of knowledge that he had absorbed in school and at univer sity. He could recall it all and he never stopped asking how and why - a classic scholar.

Henry was so focused on walking and discovery during his bachelor days that people around him went largely un-no ticed, particularly if it was an admiring woman. Others could sense the vibes but not Henry. He managed nearly forty years without a distraction.

Eventually, in 1972, following an exotic walking trip in the highlands of New Guinea, Janet made him real ise that there are other pleasures in life. So off they went, in a glass coach pulled by two white horses, to the little church at Gordon and the start of a new life. The wedding cake was cut with the bushman's saw that Henry always carried in his trusty Holden station wagon.

At last he embraced living in a community, building a home and family and extended his interests to in clude theatre, movies, art galleries, dinner parties and even wine drinking in moderation. Bushwalking had to be balanced with time required for family activities and so he had to relinquish some of his National Parks Journal duties, but never his desire to lead trips into new territory.

The incoming editor noted that "Few people have done so much, in so many ways and for such a long time as Henry has." Henry's integrity was recognised and respected by all who knew him. Occasionally this character trait created difficulties. At the end of our epic Tarkine trip, (led by Henry) along the Tasmanian coast a few years back we had to cross the Pieman River. There was no solution to this potentially dangerous crossing until about a kilometre from the river we met two fishermen in the national park, collecting their crayfish pots. They initially told us it was impossible to take us across the river because they would be seen by other residents of the permissive-occupancy settlement at Pieman, and if reported to the park ranger could lose their resident status. But after appropriate financial enticement and agreeing to say that we swam the river, we were ferried across at dusk. For three days while camping adjacent to the settlement and exploring the conical rocks area we had to maintain a lie. Henry found this deception extremely difficult for, as usual, he wanted to regale everyone he met with an accurate and detailed story of our adventure.

Henry enjoyed observing the whims of society and social change but never felt the need to adhere to the latest demands. The same old shorts and shirt, washed up well, lived on through many a fashion change. Long after many market changes his bush walking gear remained the standard old extra-heavy, lumpy, H-frame pack and a porous japara tent. He was aware of all the refinements going on but weight on the back or minor discomfort were never an issue, so why bother changing.

All that really mattered was being there.

Henry Fairlie-Cuninghame died at home, in Pymble, on 4 January 1999 after a twelve-month illness with mesothelioma. He is survived by his wife Janet and his son Robert.

The quotation by John Burroughs used on the order of service

for his funeral was one with which Henry personally identified:

"The longer I live the more my mind dwells upon the

beauty and wonder of the world. I am in love with this world; by

my constitution I have nestled lovingly in it. It has been my

home. It has been my point of outlook into the universe. I have

not bruised myself against it, nor tried to use it ignobly. I

have climbed its moun tains, roamed its forests, sailed its

waters, crossed its deserts, felt the sting of its frosts, the

fury of its winds, and always have beauty and joy waited upon my

comings and goings."

John Murray

John has been a member of NPA since 1964.

PHOTO NO 2 REDUCE BY 1/3 Henry crossing the Kowmung R, with Les Hanke Photo: John Murray

JUNE 1999 5

Join the NPA!

NPA Membership Application I/We would like to join the National Parks Association of NSW Inc. and agree to be bound by the rules of the Association.

SURNAME (block letters)

OTHER NAMES

ADDRESS

P'CODE

PHONE (H)

(W)

Annual Membership Fee (please tick appropriate box/es) ADULT $43

HOUSEHOLD $48 CONCESSION $23 Student/Unwaged/Pension (circle

appropriate category) SCHOOL/LIBRARY $50 CORPORATE $200

DONATION $ (donations of $2 or more are tax deductible)

OPTIONAL INSURANCE CONTRIBUTION $3 per person to Confederation of

Bushwalkers Insurance Scheme

I can help NPA with

Payment Options I/We enclose cheque/money order for $ being

subscription for year(s).

OR please charge my Mastercard/Bankcard/Visa (circle

appropriate category)

No.

Expiry Date

Please accept your first copy of the National Parks Journal as

receipt of membership. A separate receipt will be issued for

donations.

Signature

Date

Please post this form, with payment, to: National Parks

Association of NSW Inc., PO Box A96, Sydney South NSW 1235.

OR for credit card payments ring Kristi at the NPA Office on 02 9233 4660.

OR cut and paste this form into an e-mail to npansw@bigpond.com

Notice of AGM

Notice is hereby given to members that the Annual General Meeting of the National Parks Association of NSW will be held on Saturday 7 August at 12 noon at Jenkins Hall, Lane Cove National Park.

It will be held in conjunction with the August State Council meeting.

Any members of the Association may attend.

Tim Carroll

Hon Secretary

JUNE 1999 7

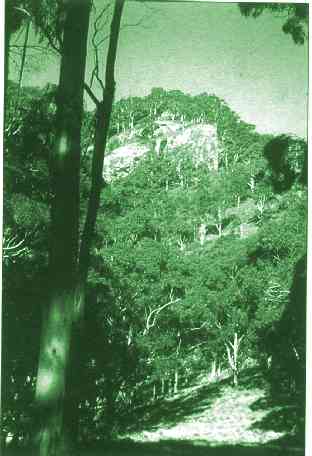

Towarri National Park

Connecting the islands in the sky

John Macris*

Around 25 kilometres north-west of Scone a new park is starting to reveal itself. This is happening in gradual stages and is arising from various land tenures, which is quite unlike days gone by when a worthwhile park could be created from one decent block of Crown land or State forest.

There are not too many more of these simple options left and hence land acquisition is becoming much more critical to reserve design. In the far west of the State the acquisition of as few as three adjacent leases will yield a quite substantial area of park.

In the eastern and central divisions properties are generally much more modest in size and this compli cates things considerably when setting out to create a reserve through acquisitions. The best example is probably Oxley Wild Rivers National Park, which started out as a scattering of former Crown land pock ets in the upper Macleay gorges. They have been gradually linked by acquiring intervening leasehold lands (around 50,000 ha to date).

Towarri National Park now exists in part, but the conceptual area supported by NPA and others could optimistically see it expand to around five times its current size and conceivably link to Coolah Tops National Park.

The land tenure of the proposal is mainly leasehold, with some Crown lands and a minority of freehold. Further complicating the tenure issue are two travel ling stock routes which are under the jurisdiction of the Rural Lands Protection Board.

Setting the scene The Great Dividing Range per forms several duties that most would be aware of - its water shed service; the popular bit down south with snow on it; housing most of the State's softwood plantations; and a fair proportion of the choice grazing country. Only a couple of small sections are within national parks, with the range's more dissected and rugged sibling - the Eastern Escarpment - enjoying the lion's share of those.

Along part of the Hunter Valley rim, the Great Di

vide deviates from its typically north-south orientation and

heads west to east for around 100 kilometres, as a relatively

narrow plateau of 800 to 1,300 metres alti tude which falls away

steeply on either side into the Hunter and Namoi catchments. This

section is specifi cally called the Liverpool Range and those

travelling between Tamworth and Sydney could not help but notice

the impressive skyline it forms, particularly when viewed from

the flat plains to the north. The range here is capped in basalt

and features a number of volcanic plugs and lava caves to

emphasise the geological history.

Along part of the Hunter Valley rim, the Great Di

vide deviates from its typically north-south orientation and

heads west to east for around 100 kilometres, as a relatively

narrow plateau of 800 to 1,300 metres alti tude which falls away

steeply on either side into the Hunter and Namoi catchments. This

section is specifi cally called the Liverpool Range and those

travelling between Tamworth and Sydney could not help but notice

the impressive skyline it forms, particularly when viewed from

the flat plains to the north. The range here is capped in basalt

and features a number of volcanic plugs and lava caves to

emphasise the geological history.

The range's altitude, volcanic soils and orientation to moist southerly winds have provided ecological niches that seem remarkably out of place when com pared to the surrounding country of open grassy plains and woodlands. At Coolah Tops tall forests of snow gums (Eucalyptus pauciflora) are found, forming one of a handful of areas outside the Australian Alps where sub alpine communities have sur vived the warming of Earth's climate over the last 17,000 years. In the central section of the range, between Mt Terell and Square Mountain, the soils and the effect of the high south facing range have provided a refuge for warm temperate and subtropical rainforest associa tions. These are essentially the most inland occurrences of rainforest patches, sitting be tween 160 and 190 kilometres from the coast. They provide habitat at the western limit for populations of rainforest fauna such as the red-necked pademelon, yellow-throated scrub wren and green catbird.

Also of interest in this section of the range is a merging of geology to the south-west of Square Mountain, into an outlying Sydney Basin escarpment and plateau area which includes the promontory-like feature of Wingen Maid. The vegetation and land scape contrasts on either side of the geological boundary are marked, with the poor soils of the sand stone/conglomerate plateaux supporting low open woodlands of schlerophyll species interspersed with cypress pine.

History of conservation initiatives A number of studies and reserve proposals over some thirty years have highlighted the wealth of natural values and scientifically significant features, but progress towards the protection of these within the national parks estate has been slow.

The Pickard report of 1970 proposed the estab lishment of a Liverpool Ranges National Park from Coolah Tops to just west of Murrurundi. The NPWS was apparently at that stage less than enthusiastic about such a reserve due to the very high perimeter-to-size ratio.

Small dedications in the 1970s at disparate locations along or near the range in cluded Wallabadah Nature Reserve (1,132 ha) north-east of Murrurundi in 1971 and Wingen Maid Nature Reserve (1,077 ha) in 1974. In 1977, as part of its rainforest conservation policy, the NPWS stated its aim to protect the rainforests of the Liverpool Range and soon after acquired a 190 ha leasehold property which was dedicated as Cedar Brush Nature Reserve.

In the 1980s and into the early 90s conservation groups focused attention on the State forests at either end of the range, proposing the Coolah Tops National Park and Ben Halls Gap Nature Reserve.

Through considerable effort by many people, not the least of which were the NPA Tamworth Namoi and Hunter branches, the available public lands in these two areas were gazetted as national parks by the State Government in 1995 and 1996.

The other event which had ramifications for the area in the early 1990s was the move towards whole sale conversion of Crown leasehold areas to freehold by the Greiner Government. A number of leasehold portions, including some dominated by rainforest, were sought for conversion to freehold - this raised the stakes in the campaign against the Government's policy. This renewed interest was timely, as the NPWS had undertaken further reference work for a proposed Towarri Nature Reserve on the tail of a floristic study of the rainforest stands by HJ Fisher of the University of Newcastle.

In 1995 around 2,500 ha of land in the upper reaches of Middle Brook were acquired by the NPWS and this was gazetted in October 1998 as Stage 1 of Towarri National Park. Obstruction from the Depart ment of Mineral Resources saw the gazettal limited to a depth of 100 metres, a disturbing precedent. Late last year all of the Crown lands in the Towarri proposal were identified as required for the Comprehensive Adequate and Representative (CAR) reserve system through the forest assessment process. In March this year about a third of these (essentially the sandstone/ conglomerate plateau areas) were added to the park, while the remainder were deferred pending considera tion of impacts on grazing permits the park additions might have (that is, what compensatory measures might be required).

Management While the NPWS's observation in the 1970s of a high boundary-to-area ratio is still the case, the nature of the land system - a natural island or archipelago sitting above cleared grazing country is probably a less difficult man agement prospect than many of our larger parks, which are mostly set in gorge country adjacent to a modified upper catchment. Here the major disturbances are all down stream of the core natural fea tures. Other management tasks like feral animal control can also capitalise on the fact that there are limited adjacent areas to serve as future restocking sources for pest animals.

Visitation to Towarri is pres ently constrained because most areas which have been ga zetted so far are surrounded by private land. As a destination for vehicle-based visitation and camping the existing Coolah Tops National Park is a much more realistic option. Due to the rarity and scientific importance of the ecosystems in the Towarri section, visitor management should focus on educa tional and limited low-key recreational use.

Here's hoping that we can report back in a few years that Towarri has blossomed from its present core segments to an expansive and viable reserve.

References

* John Macris is a member of the State Council Executive and the Reserves Committee.

Grass tree, Towarri National Park Photo: John Macris PHOTO NO 4 EXPAND TO 300%

News from the NPWS

Park demonstrates the art of ageing naturally

The Grand Dame of Australia’s parklands, Royal National Park, turns a stately 120 years old this year. Celebrations have already begun commemorating the Royal’s long and varied history as Australia’s first gazetted national park.

Hugging the spectacular coastline south of Sydney and offering 16,000 ha of native bushland, the Royal is still considered to be the result of the boldest conservation move ever undertaken by the NSW Government. As the city of Sydney grew rapidly in the late 1800s, the then NSW Premier Sir John Robertson declared the expansive tract of land to be set aside for the enjoyment and leisure of Sydney’s residents. Discoveries of coal deposits in the area made the land prime for mining and Robertson’s decision led to important environmental protection for the region.

Since its gazettal in 1879, the park has been a destination for millions of Australians and international visitors alike. The early 1900s saw the development of a rail link which brought holidaymakers directly into the park, shaping the area into a mecca for Australian honeymooners amongst others.

Since its conception 120 years ago, Royal National Park has stood as a monument to Australia’s diverse and treasured native flora and fauna. It has provided generations of visitors with a chance to experience nature on its terms, leaving a lasting reminder of the importance of environmental conservation and protection.

For more information on the activities and facilities offered to Royal National Park visitors, phone the Visitor Centre and Wildlife Shop on 02 9542 0648.

Liz

Rossiter

Media assistant

Environment News & Action

Earth Garden and the Giant

Once upon a time, but not so long ago, there was an earth friendly bunch of people who set up a publishing company in the green backwoods of Victoria (Earth Garden Pty Ltd). For many years, they happily produced magazines and books about green things, for other earth friendly people to read. Then, one day, they decided to write a book about how to use plantation and recycled timbers for building, so that our great forests would not be cut down (Forest-Friendly Building Timbers, edited by Alan T Gray & Anne Hall).

But, instead of just telling the people who already knew them, they thought, "Why don't we let all everyone know about this? Then we can all help our forests." And so they won the support of a national conservation group, The Wilderness Society (TWS), and a company who sells timber and timber products, BBC Hardware (in March this year). And lo, there was rejoicing in the land, because now we all knew about this book that would help use timber in ways that will do less harm to our beloved planet. And we could get hold of this book easily, through BBC Hardware shops.

But then, dear reader, in April was heard the sound of trampling in the forest. The National Association of Forest Industries (NAFI) and Executive Director at the time, Dr Robert Bain - told us that the book contained "information that is deceptive, misleading and unscientific", and they warned Earth Garden, and the book's editors, and BBC Hardware, and other distributors, that they should not distribute or advertise the book, for it was a very naughty book indeed, and NAFI said it had contravened the Trade Practices Act 1974.

And so it came to pass that BBC Hardware withdrew the book from sale. But Earth Garden and TWS would not be stopped. They went to the great protector of consumers, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) for help, and the ACCC said they would look into whether it was NAFI who may have breached the Trade Practices Act, if they unduly influenced BBC Hardware.

And there was much toing and froing, and TV reports, and articles in newspapers, and radio coverage, throughout the land. But the story still continues and we do not know the end yet, for NAFI has now become silent, and Dr Bain has gone to work for the AMA, and BBC Hardware are still undecided about whether they will restock the book, and the ACCC is still considering whether or not to investigate NAFI (as of mid May).

Which only goes to show that little companies can create big ripples, and big noises can lead to record book sales. So do not despair, dear reader, you too may one day make a big ripple.

Timbarra win & loss

On 9 February 1999, the Court of Appeal unanimously upheld a legal challenge brought by the Timbarra Protection Coalition (TPC) about approval of proposed extensions to the Timbarra gold mine. In response, Ross Mining applied for special leave to appeal to the High Court - this was dismissed on 14 May 1999. Nevertheless, the mine now looks set to proceed following completion of a Species Impact Statement by Ross Mining.

The TPC had appealed against an earlier Land and Environment Court decision dismissing a challenge to the development consent for extensions to the mine. This case concerned the power of the Land and Environment Court (L&E Court) to review decisions of councils relating to the impact of development on threatened species.

The TPC believes that the Timbarra mine site is an important habitat for threatened species such as the Hastings River mouse and the stuttering frog, and that Tenterfield Council did not fully address the potential impacts of the mine on these species when granting approval for the development. The February appeal win did not declare the consent void, but held that the L&E Court could consider evidence about the impact on threatened species that was not before the Council at the time it granted consent .

The decision has important implications for the protection of threatened species. If a developer understates the impacts of a development on threatened species, the Court can critically examine a development consent already granted. Councils also need to take care when assessing development applications, and ensure they properly analyse the material before them relating to impact on threatened species, or the Court may overturn the decision.

Ross Mining appear to have conceded the TPC’s point, as they have now prepared a full assessment of the impacts on threatened species as part of a new development application, and have sought a new grant of development consent. Accordingly, the TPC have withdrawn their legal proceedings.

Chris

Norton

Solicitor

Environmental Defender’s Office

Help for Hexham Swamp

Hexham Swamp lies on the outskirts of Newcastle, a part of the Hunter River estuary. Grazing and floodgates have been the main contributors to considerable alteration of the wetland's ecology.

Despite these changes, Hexham Swamp is part of the National Estate, and government has now agreed that it is worthy of financial assistance. NPA Hunter Branch is one of the many community groups who have lobbied for help for the Swamp.

The Federal Government, via the Natural Heritage Trust, has pledged $2.7 million over the next three years. As a pre-election promise, the NSW Government stated they would also contribute $2.7 million over three years, starting with $900,000 in the 1999/2000 budget. The Hunter Catchment Management Trust will coordinate the restoration, which will form a vital part of the Ironbark Creek Total Catchment Management Strategy.

The aim of the project is to reintroduce an estuarine ecosystem. This will not only improve the health and population of the native plants and animals dependent on the Swamp, but a healthier ecosystem will also benefit the local fishing and tourism industries.

Wanted WILDERNESS CAMPAIGNER The Colong Foundation requires an Assistant Director to undertake lobbying, research and a range of executive secretarial duties. Knowledge of and commitment to national park and wilderness issues, campaigning experience, writing and public speaking experience essential. A part-time applicant with agreed flexible hours of work would be considered. Wage: 3 dpw, $15 per hour |

JUNE 1999 13

BioDiversity

Putting the pieces back together again

Andreas Glanznig*

I n ten years biodiversity has leapt from obscurity to become a central plank of environment law and policy, from local councils to the lofty heights of the United Nations. It has been used to provide the umbrella for conservation approaches that move beyond national parks and threatened species to integrate conservation efforts at the regional level. This broader approach emphasises the role of off-reserve conservation efforts in biodiversity conservation.

In many ways, the phenomenal rise of biodiversity within mainstream ecological thinking about development decisions has occurred before the general public has fully come to grips with the meaning of the concept and how it relates to their lives.

Market research completed earlier this year showed that community understanding of the biodiversity concept remains at about 10% - the same level of awareness found in a major study in 1993.

This is at odds with the urgency and scale of the biodiversity `problem', considered by the 1996 National State of the Environment Report as probably Australia's biggest environment problem.

Biodiversity is commonly seen as an `out there' issue of little relevance to our highly urbanised society, compared to water quality or air pollution. Biodiversity decline happens in the Amazonia or in outback Queensland, not in my backyard. Ironically though, many Australian cities have been built in biodiversity rich areas, and urban sprawl and resulting habitat loss in reality bring us a lot closer to the biodiversity question.

The challenge is that most people are not aware of the connection between biodiversity and their welfare and lifestyles. The role of biodiversity in producing fresh water and clean air, and being the source for many of our medicines, is still not widely understood.

To turn this around, the Community Biodiversity Network (CBN), in association with Environs Australia: the Local Government Environment Network, has produced the Earth Alive Home Guide: how to conserve your local biodiversity, that includes a foreword by Olivia Newton-John.

The CBN is also working with a broad range of groups to promote biodiversity and its importance through Earth Alive! National Biodiversity Month in September. The Month embraces National Threatened Species Day on 7 September, being coordinated by the Threatened Species Network (see below), and I urge you to get involved in your local area! For a free introductory booklet on biodiversity, ring Environment Australia toll free on 1800 684447.

To find out more on biodiversity, subscribe to a free bulletin on biodiversity conservation and the implementation of the National Biodiversity Strategy, or obtain a copy of an Earth Alive! National Biodiveristy Month information kit, contact the CBN.

The CBN is hosted by Humane Society International, Australian Museum and the World Wide Fund for Nature, with core funding support from Environment Australia.

Contact: Community Biodiversity Network, Australian Museum, 6 College St, Sydney 2000.

Ph: 02 9380 7629 Fax: 02 9380 7630 Email: admin@cbn.org.au

or: earthalive@cbn.org.au

Web: www.cbn.org.au

* Andreas Glanznig is National Coordinator of the Community

Biodiversity Network.

| Bio What? The variety of nature is known as biological diversity or biodiversity. Biodiversity is more than just the number of different plant and ani-mal species that live in a region. It also includes all the variety of genetic information contained in all of the individual plants, ani-mals and microorganisms in a region, along with all the different types of ecosystems from forests to wetlands, grasslands to coral reefs, that exist in a region. |

Threatened Species Network

TSN is a national network with a coordinator in each State. It is funded by Environment Australia under the Endangered Species Program, and managed by World Wide Fund for Nature. The primary functions of the TSN are to involve the community in the recovery of threatened species and ecological communities; and build links between the community and government.

TSN has a website and a quarterly newsletter, and we are keen to hear from community groups interested in receiving the newsletter. There is also the TSN Community Grants Scheme for community groups who wish to implement threatened species projects.

On 7 September it will be Threatened Species Day with a range of events happening, and we would love to hear from any community group that may have an activity or event near that time.

To contact us in NSW: Threatened Species Network, PO Box 528 Sydney NSW 2000 Ph: 02 9281 5515 Email: ntsnnsw@peg.apc.org Website: www.nccnsw.org.au/member/tsn (Claire Carlton, Coordinator; Francesca Andreoni, Deputy Coordinator)

14 JUNE 1999

Extinction & conservation

JR Giles*

T he purpose of this article is to summarise key information on the current state and trends in global biological diversity and ecosystems, and to outline the current state of play in Australia. Much of the following material is drawn from some relatively recent documents on global and Australian biodiversity. In particular, McNeely et al. (1990) and the NSW Biodiversity Strategy have been drawn upon heavily.

Biodiversity is a relatively new word, dating from the early 1980s. It is defined in the National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia's Biological Diversity and the NSW Biodiversity Strategy as: "the variety of life forms - the different plants, animals and micro-organisms, the genes they contain, and the ecosystems of which they form a part." It has, therefore, three levels: genetic diversity within and among species; diversity among species; diversity among habitats, biotic communities and ecological processes.

Wildlife extinction rates The best current estimates are that the average background rate of extinction of vertebrates over the past 200 million years has been of about 90 species per century (Raup 1986). Myers (1988) cites a crude estimate for the extinction rate of higher plants of about one species per 27 years over the past 400 million years, increasing in recent epochs as increasing numbers of vascular plant species evolved.

A recent estimate suggests that there are 30,000,000 plant and animal species currently living on the earth, which are disappearing at a rate of between 12 and 50 species a day. This extinction rate may be higher than at any previous time (Wilson 1988a).

In relation to current vertebrate extinctions, Seal (1991) stated that "currently about 15% of taxa are critical and 15% more are endangered. This means that 3,0005,000 non-fish vertebrates are at significant risk (20-50% probability) of extinction over the next ...

10-50 years." The recently published World Conservation Union (WCU; was IUCN) Red List of Threatened Plants adds 33,798 species to the list of endangered organisms; this is 12.5% of the known plant species.

Biodiversity losses in Australia The decline in biodiversity in Australia is serious. Because the country was first occupied by Europeans in only 1788, and the biota was subject to relatively intense scientific study during the past two centuries, the decline is relatively well documented.

The most severely depleted taxa are mammals in the weight range of 35-5500gm. Many of these species have lost more than 80% of their original ranges and most are extinct in the semi-arid and arid parts of the mainland.

Habitat loss and "foreign" predators and competitors have been the major threats to these animals.

About 14.4% of Australia's known 15,638 vascular plants are listed as threatened by the WCU.

Loss of wildlife habitat Loss of wildlife habitat Loss of wildlife habitat Loss of wildlife habitat Loss of wildlife habitat Habitat destruction is the cause of most extinctions. On a worldwide basis, loss of terrestrial wildlife habitat is massive and is increasing at a growing rate. Tropical moist forests, in particular, have been/are being greatly impacted.

These forests support an extraordinarily diverse biota and are being cleared at a very rapid rate.

Citing several IUCN and United Nations sources, McNeely et al.

(1990) acknowledged the lack of precision in the estimates of contemporary rates of clearing of such forests, but conclude that this rate is likely to be at or above 0.6% per year. They further concluded that about 65% of wildlife habitats in sub-Saharan Africa and tropical Asia had been lost by 1990.

These levels are clearly not sustainable. Their impacts are not only on biodiversity, but also on global climate, rates of soil loss, freshwater and marine pollution, and ultimately on the capacity of the planet to produce food, fibre and fuel for humans.

Impact of human population The increase in recent extinction rates are related to human population size and the exploitation of natural resources. The rate of human population growth has been extraordinary. It has been estimated that in 1 AD, the global human population was about 150 million, concentrated on the coastal fringes of eastern Asia, India and the Mediterranean. The population did not double to 300 million until 1350, but by 1950 there were 2.4 billion and in 1985 there were 5 billion (Tanton 1994).

This population and its activities have had dramatic impacts on biodiversity and natural ecosystems. Diamond (1992), indicated some of the more dramatic ecological impacts of a large and increasing population size: "At present, humans are commandeering 40 percent of all the biological energy fixed from sunlight on the planet, either by JUNE 1999 15 eating, clearing the land, or grazing their animals on it. The human population is doubling every 40 years, so in 40 years from now - 2032 - we will be commandeering nearly 80 percent of all the energy from sunlight that is fixed by biological systems. By 2050 we will be using 100 percent, and we will be fighting each other in dead earnest." The assumptions implicit in the statement above are rather broad and open to challenge, specifically in relation to timeframe. In reality, this does not matter much - we humans are consuming the resources on which we depend at rates which are unsustainable in the medium term and those rates are increasing as the global population grows and strives for a better material quality of life.

Recent trends in wildlife extinctions are valuable examples of what could happen to humans, rapidly and soon. Species at the highest trophic levels in an ecosystem are those most severely affected by breakdown of the ecological processes that drive the system.

Humans are right at the top of a very complex suite of ecosystems, many of which have been greatly changed. One principle in ecology is that a stable ecosystem displaced from stability will oscillate violently until it finds a new stability. Because of the complexity of ecosystems and their driving processes, the nature of new equilibria are very difficult to predict, as are the losses sustained along the way from the old to the new stabilities.

Biodiversity conservation in Australia The Convention on Biological Diversity deals at a global level with conservaiton of biological diversity, its sustainable use and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits that derive from this use. It was ratified by Australia on 18 June 1993.

A National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia's Biological Diversity was published in 1996. The Prime Minister and heads of government of all Australian states and territories committed to implement the strategy as a matter of urgency, subject to the budgetary priorities and constraints of their individual jurisdictions.

The primary legislative framework for conservation of biodiversity in NSW is the Threatened Species Conservation Act, 1995 (TSC Act) (see also article on pp 18-20). This Act includes specific provisions for: the listing of threatened species, populations, ecological communities and key threatening processes; declaration of critical habitat; the preparation of recovery plans; the preparation of threat abatement plans; and the preparation of a Biological Diversity Strategy.

A Biological Diversity Advisory Council (BDAC) is established under the Act with broad responsibilities for advising and assisting on strategic matters relating to biodiversity conservation. Membership includes persons with expertise in science and in industry, representatives of the NSW Aboriginal Land Council, local government, learned societies and the environment movement.

The NSW Biological Diversity Strategy A Biological Diversity (Biodiversity) Strategy was drafted by the NPWS in 1995 as a framework for a whole-of-government approach to conservation. This was reworked with substantial input from BDAC and released for public comment for four months in 1997, after which the strategy was again revised.

The strategy aims to meet the objectives of section 140 of the TSC Act, and to reflect the provisions of the 1993 International Convention on Biological Diversity and the National Strategy for the Conservation of Australia's Biological Diversity.

Section 140 of the Act requires the Strategy to include proposals for: a) ensuring the survival and evolutionary development in nature of all species, populations and communities of plants and animals including appropriate protection under the Wilderness Act 1987 or the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974, and b) preparing or contributing to the preparation of strategies for ecologically sustainable development in New South Wales, including the integration of biological diversity, conservation and natural resources management, and c) an education program targeted at the community and public authorities, and d) a biological diversity research program, and e) encouraging greater community involvement in decision making affecting biological diversity.

The Biodiversity Strategy does not currently address fish as defined in the Fisheries Management Act, but it will. The Fisheries Management Act was amended in 1997. The Amendment Act makes specific provisions for conservation of threatened species, populations and ecological communities of fish and marine vegetation; and to ensure ecologically sustainable development, including the conservation of biological diversity. It also makes provision for extension of the Biodiversity Strategy to include fish and marine vegetation.

PHOTO NO 5 EXPAND TO 300% Rainforest - a disappearing resource (Towarri area) Photo: John Macris

16 JUNE 1999

Objectives and actions of the strategy

The Biodiversity Strategy was launched formally by the Minister for the Environment on 9 March 1999. Its objectives and actions fall under five major headings: a) Community consultation, involvement and ownership b) Conservation and protection of biodiversity c) Threatening processes and their management d) Natural resource management e) Improving our knowledge.

In order to adequately assess the financial implications of the Strategy as well as seek a coordinated and cooperative whole-ofgovernment approach, a Biodiversity Strategy Implementation Group has been established. This Group is chaired by the Chair of BDAC and includes representatives of NPWS and other government agencies.

BSIG worked very well during 1997 in refining priority actions under the strategy; developing a framework for inter-agency cooperation on implementation of the Strategy; and developing a funding proposal for implementation of priority actions.

Conclusions A lot of species, populations and habitats are under threat in NSW.

Conservation is costly and is resource limited. In expanding the conservation agenda to include the full spectrum of biodiversity, additional resources are essential and must be seen to be managed effectively and responsibly. Careful planning and monitoring must be put into place to ensure, as far as possible, that adequate resources are directed into priority areas with a close eye to rapidly detecting those which are proving to be unsuccessful and expensive.

Taxonomic and ecological knowledge is pivotal to conservation planning and management.

We need to know what species, populations and critical habitats we have; how many there are; where they are; their rates of increase; what drives these parameters; and how to preserve key biotic elements and ecological processes. However, realities dictate that we cannot spend all our resources on research, survey and improved reference collections; finding the most appropriate balance in resource allocation involves a set of important and difficult strategic decisions.

Allied to the above is the fact that it is relatively easy to obtain support for the conservation of well known and appealing organisms. It is not easy to muster support for animals and plants that are threatening, repulsive (to some), very small or poorly known.

A large component of biodiversity conservation centres on littleknown or appreciated organisms and the ecological processes in which they are involved. Selling the values of such organisms to a sceptical community will be a major task.

Efficiencies in resource distribution are likely to be achieved by timely and effective action to address processes that threaten many species, populations and/or critical habitats in comparison with a species-by-species approach.

Threatening processes in particular will not be easy to deal with.

In my view the classical paradigms for conservation are proving to be inadequate to meet the urgent and growing needs of biodiversity conservation and it is time to look at different paradigms.

A whole-of-government approach is essential, as is community acceptance of the objectives. Reservation of land is not an adequate conservation tool to meet current conservation objectives - a lot more technical and communitybased work needs to be done on wildlife conservation off reserves.

It is unlikely that every species, population or critical habitat can be conserved. Among the difficult decisions will be determination of the species and populations that will be sacrificed in order to free up resources for others. This has been addressed in the USA by establishment of the so-called "God Committee" under the US Threatened Species Act, in an attempt to formally address this dilemma on a national scale. Membership of such a Committee might not be seen by many conservationists to be a joy and a privilege.

A lot of challenges confront us.

Many of these are related to the management of human needs, aspirations and influences on the landscape and its dependent biota. To the extent that this is true, selling and science are equally important in effective conservation of biological diversity.

References

This article is an extract from a paper given at the NPA Biodiversity lecture series on 8 March 1999.

* Dr JR Giles is General Manager of Scientific Policy and Research with the Zoological Parks Board of NSW; and is Chair of the NSW Biological Diversity Advisory Council.

JUNE 1999 17

Honeybees & biodiversity

Kristi MacDonald*

Do honeybees have a detrimental effect on the environment and do they threaten biodiversity? Is beekeeping an appropriate use of our conserved areas? These questions have been debated by conservationists and apiarists for some time now (see also page 9, NPJ August 1998).

This article will highlight some of the deleterious effects honeybees can have on biodiversity.

Apis melifera (the honeybee) was introduced into Australia in 1822 to provide food and food sweetener, and to pollinate crops.

The species rapidly became naturalised throughout much of the continent. There are currently 673,000 registered hives in Australia and an unknown number which are unregistered (Gibbs & Muirhead 1998). An efficient gatherer of nectar and pollen, the honeybee is found in most habitats including eucalypt and rainforests, farming land and urban areas (Gibbs & Muirhead). Honeybees utilise the flowers of at least 200 native plant genera (Paton 1996) and in some habitats 30-50% of the species in an area may be visited. These species would normally be pollinated by wind, birds, insects or mammals (Gibbs & Muirhead 1998).

The beekeeping industry relies heavily on public land for access to the floral resources necessary for producing honey. However, some of this public land is contained within the national parks estate. Concerns have been expressed that beekeeping is a commercial activity which utilises an exotic animal - is this a suitable activity in areas which have essentially been set aside as sanctuaries for our native plants and animals?

Potential impacts

Results of research conducted to determine the potential impacts of the honeybee are mixed. Gross (June 98) conducted a five-year study looking at the impacts of the honeybee on the native bee - native plant relationship. This research demonstrated that honeybees can negatively impact on native ecosystems. It was concluded that honeybees reduce seed set in native species and aggressively deter native bees from flowers.

Paton (1996) also suggests that honeybees can influence the production of seed. While some plants will experience reduced seed set, others will be enhanced (increased seed set) after the introduction of honeybees. However, this does not necessarily imply that a benefit is being provided to those plants.

Negative long-term effects could be experienced if the plants reproduce above normal levels to the detriment of other native plants, thus threatening local biodiversity.

He further suggested that for many plants honeybees were the most frequent floral visitor, often consuming more than half of the floral resources being produced.

This can affect other visitors to flowers, such as birds.

For instance, the responses of honeyeaters after the introduction of honeybees depends on the amount of nectar and pollen being produced by plants. In Banksia ornata heathlands, where there were surplus resources available, the number of honeyeaters did not change. However, in patches of Callistemon rugulosus, New Holland honeyeaters increased the size of their feeding territories and decreased the frequency with which they visited each flower.

Threats to invertebrates have also been noted. Honeybees may compete with native thynnid wasps, for example, which are needed for pollination of certain orchids (Denny 1991).

Other negative impacts on our biodiversity are associated with activities related to beekeeping.

Accessing hives has the potential to introduce pathogens and weeds into conserved areas via the wheels of motor vehicles.

Additional research is required on a wide diversity of native plants and nectivorous animals to conclusively determine the effects of the honeybee on Australia's biodiversity. Until such time that these effects (either detrimental or beneficial) are fully evaluated the precautionary principle should apply.

On 22 May 1998, the then Minister for the Environment, The Hon Pam Allan, announced to the NSW Apiarists Association that she had approved intergenerational transfer (IGT) of beekeepers' licences.

Prior to this, licences only applied for the life of the licensee and could not be transferred. Hive sites currently within the national parks estate may therefore remain indefinitely as licences pass on to beekeepers' descendants.

References

* Kristi MacDonald has a BSc (Hons) from the University of NSW, and is NPA's Administrative Officer.

18 JUNE 1999

Conservation of species

Ian M Johnstone*

I t is interesting to look back at legislation aimed at protecting native plants and animals.

Knowing something about how we got here may help us feel more confident about the way forward under the Threatened Species Conservation Act, 1995 (TSC Act).

History of legislation

In 1879 the NSW Native and Imported Game Act was passed "To secure the protection of certain birds and animals." Section 2 provided a penalty "Not exceeding two pounds ... for any person wilfully shooting, capturing, killing, taking or destroying any native game or imported game between 1 August and 20 February next following." Section 3 provided for a penalty of up to ten pounds for anyone who used firearms for shooting native game or imported game when the firearm had a greater length of barrel than 6 feet, or with a bore exceeding 1 inch in diameter, or when the charge when loaded exceeded 4 drachms of gunpowder and 3 ounces of shot! The list of native birds you could shoot between 20 February and 1 August, so long as you used a short, and presumably less accurate, firearm, sadly included the emu, brolga (now TSC Act vulnerable), bustard (now TSC Act endangered), "wild goose of any species" (which presumably included the cotton pygmy-goose, now TSC Act endangered, and the magpie goose, now TSC Act vulnerable) and wild duck of any species (presumably including blue-billed duck and freckled duck which are both now TSC Act vulnerable). Those early "sportsmen" must have been desperate for something to shoot for "sport" or eating.

In 1901 the Birds Protection Act was passed. Like the Native and Imported Game Act 1879, it had the apparent purpose of protecting birds from us, but the real purpose of protecting birds for us. It provided a closed season and a penalty of five pounds for "whosoever during the closed season wilfully kills, captures, or injures _ any scheduled bird" (Section 6). The schedule has a list of 13 "foreign birds" and 48 "Australian birds".

This total of 61 contrasts with the 10 birds in the 1879 Act.

In 1903 came the Native Animals Protection Act. Once again animals were listed in a schedule.

Inititally there was a period of absolute protection for 14 months from 5 December 1903 to 31 January 1905, presumably to allow these animals to breed up a bit.

Animals listed included red kangaroo, wallaroo, native bear (koala), three species of wombat, platypus and echidna - a total of twelve native animals which seemed then to deserve protection. Presumably these did benefit from that protection, because the only one now in the TSC Act schedules is the koala, which is vulnerable.

The trouble is that 19 native mammals, which never made it into any schedule of closed seasons for protection, had already been wiped out by about the time the Native Animals Protection Act was passed. For example, the western quoll was last seen about 1857, the pig-footed bandicoot wasn't seen after 1900, and the eastern harewallaby had gone by 1890, and so on. The dishonour roll of genocide appears as Part 4 of Schedule 1 of the TSC Act which lists 25 "species presumed extinct". The schedule uses the word "presumed" advisedly, because there have now been numerous examples of species thought to be extinct being rediscovered.

The Birds and Animals Protection Act 1918 repealed both the Birds Protection Act 1901 and the Native Animals Protection Act 1903. The Minister declared an open season by notice in the Government Gazette. This time "protected bird or animal" meant any bird not mentioned in the first schedule and any animal not mentioned in the second schedule, so you could shoot with impunity any of those on the list.

The animals listed in the second schedule included the tiger cat (quoll) which is now TSC Act vulnerable, brushed-tailed rat kangaroo (Bettongia penicillata) and Gaimard's rat kangaroo (Bettongia gaimardi), both of which are now TSC Act presumed extinct! The Act explicitly stated that it did not apply to "reptiles, or to rats or mice of any species" (Section 1). Now the TSC Act lists four native mice as endangered; four native rats and six native mice as presumed extinct; and two native rats and four native mice as vulnerable.

The first legislative protection for native plants in NSW was the NSW Wild Flowers and Native Plants Protection Act 1927 (as amended in 1931 and 1945). This primitive Act merely gave the government power to "notify by proclamation published in the Gazette that any wild flower or native plant specified in the proclamation is protected under this Act throughout the whole State or in any part thereof _ For a limited or unlimited period" (Section 3).

The Fauna Protection Act 1948 repealed the Birds and Animals Act 1918. This Act worked on a similar principle to the Act it repealed. "Protected fauna" meant JUNE 1999 19 any fauna not mentioned in the first schedule. The Minister could by notice in the Gazette declare an open season for "such protected fauna as may be specified in such notice" (Section 18). For instance, the northern species of hairy-nosed wombat was unprotected in twelve pasture protection districts and some parishes in a third pasture protection district - it is now TSC Act presumed extinct.

Under Section 20 the Governor could from time to time by proclamation declare any protected fauna to be rare fauna, and four mammals and eleven birds were declared as such. The list in the TSC Act, compiled almost fifty years later, has 241 fauna either presumed extinct, endangered or vulnerable, and 450 plants. Since the TSC Act came into force 16 more endangered species of vertebrates and plants and six endangered species of invertebrates have been added to the schedule.

In 1967 the National Parks and Wildlife Act was passed, then in 1974 it was repealed by a new National Parks and Wildlife Act (NPW Act), as was the Wild Flowers and Native Plants Protection Act 1927 and the Fauna Protection Act 1948. The 1974 Act followed the tradition of listing unprotected fauna and it also listed endangered fauna. Schedule 12 listed as endangered eight mammals including the bridled nailtailed wallaby (TSC Act presumed extinct), the yellow-footed rock wallaby (TSC Act endangered) and the eastern native cat (eastern quoll) (TSC Act endangered).

The schedule also lists 28 bird species as endangered including the grey falcon, which had the misfortune to be listed under the Fauna Protection Act 1948 as unprotected but which was removed from that list in 1951 and is now in the TSC Act as vulnerable.

The 1974 Act prohibited the taking or killing of any protected fauna by using "any firearm of a kind other than the kind habitually raised at arm's length and fired from the shoulder without other support" (Section 111). So pistols and hand grenades were out! For the first time it became an offence to take or kill a snake, unless the person "could reasonably have believed" that "the snake was endangering, or was likely to endanger, any personal property." (Section 112) In 1991 the landmark case of Corkill v Forestry Commission of NSW was heard by the Land and Environment Court (73LGRA126 and upheld by the Court of Appeal 73LGRA247). John Corkill of the North East Forest Alliance succeeded in an action taken under Section 176A of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 to prevent the Forestry Commission from logging 450 hectares of Chaelundi State Forest, north of Dorrigo. The logging would have breached the Act, which made it an offence to take or kill any protected fauna (Section 98) or any endangered fauna (Section 99). In his judgment, Judge Stein held that thirteen endangered and nine protected species would be put at risk if the logging proceeded.

The Endangered Fauna (Interim Protection) Act was passed in 1991. This Act was the Government's response to the debacle of the Chaelundi decision that the Forestry Commission was subject to the law about destroying threatened species, just like everyone else. Rather shamefully this "interim" Act was renewed year after year until the TSC Act took over from 1 January, 1996.

Three patterns emerge from the historical survey of legislation: i. Legislation has tended to follow rather than to prevent extermination. When we realise and acknowledge what we have been doing, we determine not to do it any more, and we put it all in fine words embodying noble intentions in an Act, hoping that will stop us doing it. It is as much a penance as a prevention, as much a regret as a remedy, and more of an owning up than an improvement.

ii. Gradually we are accepting that fauna and flora were not made for our use. Early Acts seemed to protect animals and birds from us, but really protected them for us.

iii. Governments and government bodies have always offended against conservation laws as much as any private people have. The Forestry Commission, for instance, has shown disinterest for the potential destruction of old growth forests except when its actions are questioned by a court, as at Chaelundi. Now the NPWS has the legal responsibility for threatened species, populations and ecological communities and so far, to the best of my knowledge, has not declared a single critical habitat area nor scheduled any threat abatement plans, and has gazetted only one recovery plan.

The TSC Act

The TSC Act came into force on 1 January, 1996. It is administered by the NPWS.

PHOTO NO 6 CROP SIDES AS MARKED & EXPAND TO 400% The koala was protected under the 1903 Act, but is now listed as vulnerable under the TSC Act Photo: Ann Sharp/Australian Koala Foundation

20 JUNE 1999

When discussing threatened species it is essential to think things not just words - living things, rare things, unique-to-Australia things, some of our most precious things and, like Julie Andrews in the song, some of our favourite things. While we are busy working, watching cricket, wearying ourselves with human interactions, out there in the ever-diminishing unspoilt natural places we choose to call the bush, there are animals and plants all doing their own thing - all striving, adapting, and surviving, and doing it more sustainably and successfully than we do.

The TSC Act has 10 Parts, 157 Sections and 3 Schedules. The major operative parts are: Part 2: Listing of Threatened Species, Populations and Ecological Communities and Key Threatening Processes. There are elaborate procedures to enable any person (Section 19) to nominate a species, population, or ecological community for inclusion in Schedule 1 of Endangered Species and Schedule 2 of Vulnerable Species.

It sets out how the Scientific Committee deals with these nominations - it must make a determination within six months of the nomination and must give reasons for the determination (Section 23). This is so different from the early legislation, which simply provided that the Minister could add or subtract from the schedule in 1903, 1918, 1948 and so on.

Part 3 Critical Habitat of Endangered Species, Populations and Ecological Communities. This time it is the Director General of NPWS who is responsible for identifying critical habitat after consultation with the Scientific Committee. Then the Director General refers the recommendation to the Minister, who consults with other ministers and eventually declares critical habitat, which is then made public (Sections 37 to 52).

Part 4 provides for Recovery Plans for threatened species, populations and ecological communities. It is up to the Director General to prepare a Recovery Plan (Section 56) for approval by the Minister (Section 65), which is then published in a newspaper circulating generally throughout the State, and then, if appropriate, in a local newspaper.

Part 5 provides for Threat Abatement Plans (TAPs) to manage key threatening processes. It appears that, despite the number of key threatening processes now listed, there have not been any TAPs prepared. Once again it is up to the Director General to prepare TAPs (Section 74) and up to the Minister to approve of them (Section 83).

Part 6 provides for licences to be granted to harm or pick threatened species, populations or ecological communities, or damage habitat. Section 94(2) lists eight factors the Director General must take into account before granting a licence. The Director General may require a Species Impact Statement (SIS) to be prepared in accordance with Sections 109 to 113. The licence may extend to protected fauna and protected native plants under the NPW Act 1974 as well as to threatened species.

Part 7 provides for other conservation measures including stop work orders. The Director General may make a stop work order under Section 114, which lasts for only 40 days, or for an extension of a further 40 days under Section 117.

Section 121 provides that the Director General may enter into "a joint management agreement with one or more public authorities for the management, control, regulation or restriction of an action that is jeopardising the survival of a threatened species." It should be pointed out however that the TSC Act binds the Crown (Section 142), so there should be no more room for argument, as there was in the Chaelundi case, that the protection for threatened species does not include protection from, say, the Forestry Commission.

Part 8 establishes the Scientific Committee, which is responsible for the lists of endangered and vulnerable species.

Part 9 establishes the Biological Diversity Advisory Council and the procedure for making and amending the Biodiversity Strategy (see also article on pp 14-16). The draft Strategy has been widely discussed and is at present under consideration. Section 147 provides for Restraint of Breaches of the TSC Act, and any person may bring proceedings in the Land and Environment Court for an order to remedy or restrain a breach of the Act.

NPWS has now issued four information circulars about the Act, with details about the schedules, the Eight Part Test of Significance, scientific licences and critical habitat.

Although there has been a lot of activity following the passage of the TSC Act, there appears to have been limited action concerning:

Final thoughts

Try as we might to make the world adapt to our use and convenience, we find eventually that we must continue to adapt to it. The world is not made especially for our use, any more than it was made espe cially for ants or antelopes, mice or mosquitos, worms or wombats.

They all manage somehow to survive, and so do we. It is incred ibly arrogant and short sighted for us to imagine we can bring about the disintegration and dislocation of ecosystems, and the disappear ance of species, without this even tually affecting us - we are all part of this one world.

* Ian M Johnstone is a solicitor and a NPA member.

JUNE 1999 21

Getting involved in protection of marine biodiversity

Craig Bohm*

T he NSW coast needs your eyes, your ears, your typing your talents! Much activity in the marine environment is afoot and requires the interest and involve ment of active coastal dwellers! On top of the `Activities List' (in my books, anyway) are these three - Aquaculture, Coastal Fisheries and Marine Parks.

Aquaculture

Coastal aquaculture in NSW in cludes farming of caged finfish

(such as snapper and mulloway), shellfish (such as Sydney rock

oysters, blue mussels), crusta ceans (such as prawns). Most

coastal aquaculture systems are intensive; that is, utilising

tanks, cages, string longlines or small earthen ponds to produce,

feed and grow out commercial species.

The main environmental issues:

You can get get involved by:

Coastal fisheries

The NSW commercial fishery is divided into 9 fisheries: Ocean Trap and Line, Ocean Haul, Ocean Fish Trawl, Ocean Prawn Trawl, Estuary Prawn Trawl, Estuary General, Eastern Rock Lobster, Abalone and Sea Urchin and Turbin Shell Fishery. Fishers may hold endorsements (permits) to fish in any number of these.

The day-to-day management of these fisheries falls to Manage ment Advisory Committees (MACs). Each MAC comprises representatives from industry, NSW Fisheries, fisheries research and conservation. MACs report to the Ministerial Advisory Council on Commercial Fishing, and to the Minister for Fisheries.

Representation of conservation ists on the MACs and Ministerial Advisory Councils (and a range of other initiatives) is now coordi nated by the NCC. NCC employs a fisheries officer to facilitate conservation representatives' input to management processes, and to track policy and legislative developments.

The main environmental issues: