Editorial

Editorial

NPA NEWS 4

Calling all trades;

Membership - Hands up for benefits;

New Executive;

Wanted - a creative artist;

Jobs, jobs, jobs

COVER STORY

A shrimp by any other name ... 5 by Kristi

MacDonald

ENVIRONMENT NEWS &

ACTION 7

Parks service budget & restructure;

Walk against woodchips;

Biodiversity Act conference;

Plant conservation;

Mona Vale link threat;

NPWS Advisory Committees;

Minister for the Environment

FEATURES

Waterways

- logging, boating & damming:

"We

will meet them on the beaches ..." 9 by Brian Everingham

Durras: enduring heart 11

by Geoffrey Bartram

Damming the planet

13 by Stuart Blanch

The pitfalls of mining:

It's time! to stop peat

mining 14 by Phillip Kodela

Mining - Negotiating

the pitfalls 15 by Anne Reeves

Koongarra -

Kakadu's sword of Damocles 17 by Allan Fox

Mining in the far west 19

by Kathy Ridge & Jenny Guice

ACTIVITIES PROGRAM

(Supplement following p 12)

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 20

REVIEWS 22

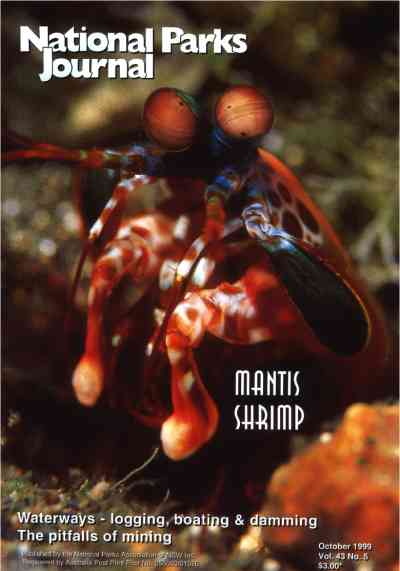

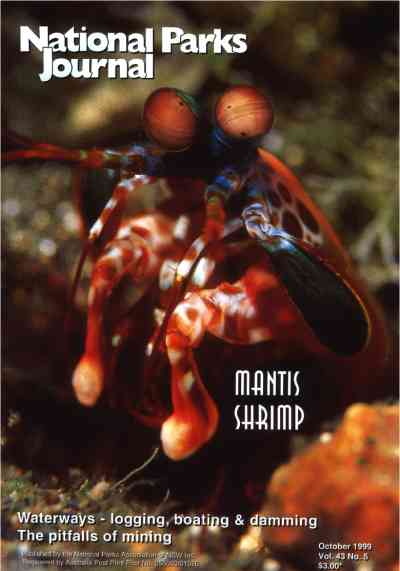

FRONT COVER: Mantis shrimp Odontodactylus scyllarus, which can

grow up to 18 cm long (Photo: Michael Aw Pictures)

| About the National Parks Journal | National Parks Association of New

South Wales | Subscribe

or join now |

Woodlands at the Frontline

The slaughtered eucalypts lay abandoned, broken and tumbled

together as they had fallen. Twenty-four mature box trees up to

20 metres tall had been destroyed for no discernible reason.

Elsewhere, a dozen large ironbarks lay uprooted and smashed for a

minor roadwork, others again had been felled and left to rot in a

drainage line.

These were depressing enough, but they were merely the

punctuation marks in a woodland that seemed to have more stumps

than living trees. The woodland, a small State Forest just out of

Gunnedah, is being intensively managed for cypress-pine timber

production, with the attendant maze of logging tracks, timber

debris and log dumps.

The treatment of the box and ironbark reflects the lack of

commercial value and hence concern for most of the remnant

ironbarks and box in the Central West forests.

Sadly, the forest managers appear ignorant of their enormous

value for nature conservation and the protection of biodiversity.

The ironbarks in particular provide the critical shelter hollows

for so much of the forest wildlife including parrots, bats, owls,

gliders and lizards, as well as providing nectar from their

extended and prolific flowering.

Ironically, the ironbarks of the Central West woodlands are

now under great threat because of a new commercial use identified

for them. The New England Tableland woodlands are also threatened

by extraction of New England blackbutt, silvertop stringybark and

messmate for the same purpose.

The NSW Government is seriously considering a plan by a

Western Australian mining company to log and burn 160,000 tonnes

a year of ironbarks and other selected eucalypt species from the

western woodlands.

These trees will be used to make charcoal to feed to a silicon

smelter at Lithgow (see NPJ August 1999). NPA considers this

proposal to be completely irresponsible, akin to hunting whales

or woodchipping old growth forests. But at this stage we cannot

even get an assurance from the government that a full

environmental impact assessment will be made.

The proposal is being fasttracked by a special unit within the

Premier's own Department, so strong is the attraction of new jobs

at Lithgow, a depressed industrial town in the heart of an ALP

marginal rural seat. Yet this is also a government which has

encouraged rural landholders to preserve and enhance remnant

woodlands on their properties, and has introduced legislation to

protect native vegetation. Indeed, in the New England Tablelands

alone there are hundreds of people who are helping to establish

wildlife corridors and other measures to protect the woodlands

and their biodiversity.

These people will quickly understand the hypocrisy of the

Government's position. This proposal attacks the very heart of

biodiversity in western NSW, the islands of State forests in a

sea of agriculture, whilst farmers work to connect these very

refuges with a network of wildlife corridors. It also pre-empts

the promised regional conservation assessment for the western

forests and woodlands, which was to determine the extent and

location of the conservation reserves, new national parks, which

are needed for the long-term protection of nature in the west.

Noel Plumb

Executive Officer

The South Coast forests need your help NOW - please see the

enclosed "Wonderland" brochure.

N PA is facing some significant challenges in seeking to

promote the cause of national parks and nature conservation in

the new millenium. We have a State Government which is complacent

with its large majority. Staff in the office of the

"green" Premier are working on projects which are a

serious threat to biodiversity in western New South Wales.

The restructuring of the National Parks and Wildlife Service

is likely to reduce the capability of the Service to achieve

best-practice management of our national parks and nature

reserves. The parks are also under threat from user groups who

conveniently ignore their impact on the park landscape and

natural values.

NPA State Council has elected a new Executive team to meet

these challenges. We are working to build membership in the

Association and to expand the range of member activities and

benefits. We are also working to protect national parks

throughout the State, and to protect the poorly reserved regions

in western New South Wales.

The Association has been fortunate that the support and

involvement of members has helped it make conservation gains in

past years. We need to ensure that our work continues to

contribute to the protection of the NSW landscape.

Roger Lembit

NPA President

4 OCTOBER 1999

NPA News

JOBS! JOBS! JOBS! JOBS! JOBS! JOBS! JOBS! JOBS! JOBS! JOBS!

JOBS! JOBS! JOBS! JOBS! JOBS!

We have some challenging honorary jobs. Flexible hours, great

job satisfaction and as many cups of tea as you like!

- Personal Assistant to the Executive Officer Noel Plumb

needs someone at least one day a week to help with

research, filing, appointments, documents, etc, etc. If

you know Word for Windows and e-mail, great - if not, we

will train you.

- Library team We need your help with our library. Some

experience is best but we will train if you can help on a

weekly basis.

- Membership promotion Do you have writing skills, people

skills, promotion skills or media contacts? Please help

us promote NPA and our great walking and conservation

programs. Work with a small volunteer team to build NPA

through positive promotion.

If you are interested please call Noel Plumb any time on 9233

4660.

Membership - Hands up for benefits

NPA will be providing its members with additional benefits

through the issue of a membership card in November. The card will

entitle the member to discounts from a variety of shops and

services. If you have any bright ideas about who could supply

discounts (such as yourself, or an organisation you work for),

please phone Michelle on 02 9233 4660, or fax 9233 4880, or

e-mail npansw@bigpond.com

Michelle Johnston, Membership Officer

New Executive

A new Executive of State Council was elected at the Annual

General Meeting on 7 August: President Roger Lembit; Senior

Vice-President - Stephen Lord; Junior Vice-President - Anne

Reeves; Secretary - Brian Everingham; others: Beth Michie, Mike

Thompson, Pip Walsh, Vivien Clayphan-Dunne, Tom Fink. We will

tell you more about them in the next issue.

Wanted - a creative artist NPA would like a

design for a cloth badge that can be sewn on a backpack or shirt.

It can be any regular shape, and should not be larger than 75 mm

(or 3") across. The idea is to promote NPA, so the badge

should display "National Parks Association of NSW Inc".

The Executive of State Council will be the selection panel. Your

reward will be seeing your design on the backpacks of your

friends! So let your imagination go and send us your ideas, by 1

January 2000. Please send your entry to John Clarke, NPA, PO Box

A96, Sydney South 1235.

Calling all trades

NPA Head Office is moving to another city location in December

and we need help from carpenters, builders, electricians. Light

work for no pay, but great job satisfaction. Ring 9233 4660

today!

OCTOBER 1999 5

A shrimp by any

other name ...

Kristi MacDonald*

PHOTO NO 2 EXPAND BY 3.25 Mantis shrimp, Erugosquilla grahami

Photo: Shane Ahyong/Nature Focus 6 OCTOBER 1999

A recent find by Shane Ahyong (a member of the Department of

Marine Invertebrates at the Australian Museum), highlights just

how little we know about our marine life, even within the waters

of Sydney Harbour. Erugosquilla grahami, a large predatory mantis

shrimp found in the waters east of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, has

only recently been named scientifically, although Shane suggests

that this shrimp has probably turned up at the fish markets and

been confused with a related species, Oratosquilla. The find also

exemplifies our ignorance about invertebrates in general.

Erugosquilla grahami, named by Shane in honour of Ken Grahame

at NSW Fisheries, belongs to the order Stomatopoda and is part of

the family Squillidae. There are approximately 500 species of

mantis shrimp worldwide, with about 130 species found in

Australian waters (such as Odontodactylus scyllarus, pictured on

the front cover, whose habitat ranges through the Indo-Pacific

including Australia). It was previously thought that only three

species inhabited Sydney Harbour, however, Shane's research has

uncovered at least twelve species of mantis shrimp there.

This particular species of mantis shrimp grows to

approximately 20 cm, although other species of stomatopods can

grow up to 40 cm. A bottom dweller, it looks like a cross between

a praying mantis and a lobster, and is distinctively coloured

purple and blue with banded antennae.

Feeding on other shrimp and fish, Erugosquilla grahami has the

ability to impale its prey in 5-8 milliseconds, and is claimed to

be one of the fastest moving predators on earth. It has a

specialised eye structure with each eye capable of binocular

vision. Such specialised eyes suggest that they also have highly

specialised brains and nervous systems, in order to be able to

process all that information. Such eye complexity is seen in no

other invertebrate. There are plans for further research on this

species for neurological and behavioural studies.

Marine life and the threats it faces With most Australians

living on or close to the coast, our coastal and marine

environments are highly sensitive to the effects of pollution and

development.

Threats to these communities include habitat loss and

degradation, trawling, harvesting and introduced species, amongst

others.

Sydney Harbour is a major estuary and the land which surrounds

it has been extensively modified by development. Activities

surrounding the Harbour can lead to severe environmental

degradation within the Harbour itself.

On the night of 2 August, 1999, Sydney Harbour fell victim to

an oil spill from the Italian ship, Laura D'Amato. As it was

being unloaded at the Shell Refining Terminal at Greenwich (Gore

Bay Terminal), 80,000 litres of light crude oil was spilt into

the Harbour.

Oil spills will affect individual marine species differently.

Depending on their form and chemistry, oil spills can cause a

range of physiological and toxic effects. Crude oil can stick to

the feathers, fur and skin of marine species, as happened with

the penguins in Sydney Harbour. Sea birds, including penguins,

are particularly sensitive to both internal and external affects

of crude oil and its refined products. Contact with crude oil

causes feathers to collapse and matt, changing the insulation

properties of feathers and down which can then lead to

hypothermia. Body weight can decrease, skin can become irritated,

foraging instincts inhibited and poisoning can occur (Australian

Maritime Safety Authority, 1998).

But what about mantis shrimp? The public would not be so aware

of the effects of the recent oil spill in Sydney on marine

invertebrates: the effects are not as immediately noticeable as

that seen with the penguins.

Mantis shrimp are near the top of the food chain in the

benthos (flora and fauna found at the sea bottom), and hence are

adversely affected by pollution in the Harbour, including oil

spills.

Volatile organic compounds are slowly released from the crude

oil, which can cause damage to plankton, including the planktonic

larval stage of mantis shrimp. These organics are directly

absorbed by the shrimp across their gills and membranes, and

ingested via their food sources. They biologically accumulate

through the food chain, the highest concentrations being found in

the prey of mantis shrimp.

However, by far the biggest threat to mantis shrimp is

trawling. These shrimp are victims of bycatch as fisherman target

prawns, crabs and squid.

Protection of the marine environment Current attention to the

protection of the marine environment pales in comparison to that

afforded our terrestrial environments. Historically, marine

protected areas - specifically protected rather than being a mere

extension of coastal protected areas - have been declared under

fisheries legislation (Australian Committee for IUCN, 1994).

These were generally small, discrete areas, and commonly the same

restrictions as those placed on land-based national parks were

applied.

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975 represented a

break from this pattern, and allowed for the establishment of the

world's largest marine protected area, the Great Barrier Reef. A

holistic approach to marine conservation was finally adopted. In

NSW the Marine Parks Act 1997 established the Marine Parks

Authority to manage marine parks in NSW. Some marine parks have

now been established in areas recognised for their unique

characteristics and are consequently protected from activities

which damage the marine environment. Zoning plans prepared for

each park protect biodiversity and resource use within the park.

Following that Act, legislation that provides for the

protection of all threatened fish and marine plants native to NSW

waters was passed in 1997, coming into effect in July 1998.

Threatened species provisions were included in amendments to the

Fisheries Management Act 1994 (FMA), and resultant changes in the

Environment Planning and Assessment Act 1979 integrated

consideration of threatened fish and marine plant conservation

into the planning and assessment process.

The threatened species provisions of the FMA allow for the

listing of threatened species, populations and ecological

communities; however, to date this list remains small with only

six species listed as either endangered (three species) or

vulnerable (three species). This may seem positive, but the lack

of information available about our marine ecosystems means we do

not know enough to determine how safe or out of danger our marine

species really are.

Recently, the Endangered Species Advisory Committee, appointed

by the Federal Minister for the Environment, sought advice from

government agencies, museums, universities and other relevant

societies and individuals about marine species, specifically

non-commercial invertebrates and plants. A summary of those

submissions (Environment Australia, 1998) emphasises our lack of

knowledge.

The abundance and diversity of our marine biota, coupled with

our limited knowledge of the processes which affect it, are

highlighted as a concern. The summary notes the importance of

increasing our systematic assessment of marine biota, requiring

increased survey, taxonomic description and research work.

Some of the respondents argued that it is more realistic to

protect particular habitats and ecosystems than to look at marine

conservation at a species-by-species level. Nonetheless, others

argued that there is an urgent need for an increased knowledge of

marine biota at the species level, since changes in systems

cannot be assessed without good baseline information at the

species level.

The find by Shane Ahyong in Sydney Harbour of a large shrimp

previously unnamed adds weight to the argument that we know very

little about our marine environment, particularly invertebrates.

It also provides an insight into the diversity of marine life

that lives on our foreshores. Despite the threats faced by our

Harbour, it is encouraging to learn that it hosts such a variety

of life.

References:

- Australian Committee for IUCN (1994) Towards a Strategy

for the Conservation of Australia's Marine Environment.

Occasional Paper Number 5. ACIUCN, South Australia.

- Australian Maritime Safety Authority (1998) The Effects

of Maritime Oil Spills on Wildlife including NonAvian

Wildlife.

- Burke's Backyard (1999) Burke's Backyard Fact Sheets -

New Mantis Shrimp. Website posting.

- Environment Australia (1998) National Marine Invertebrate

and Plant Conservation Issues. Threatened Species and

Communities Section, Biodiversity Group, Canberra.

* Kristi MacDonald has a BSc (Hons) from the University of

NSW, and is NPA's Administrative Officer. Shane Ahyong's

assistance with the writing of this article is gratefully

acknowledged.

Environment

News & Action

Parks service budget and restructure

In June, I reported that the NPWS budget had been maintained, and

even increased for specific items, despite pressure from the

Treasury to cut funds for the NPWS (NPWS at the Frontline, p 3).

We thought that we had been successful in this debate in view of

the commitment made by the Government before the election that

the NPWS budget would not be reduced.

We are now dismayed to find that the present NPWS

restructuring is being driven by a desire to find so-called

`efficiency' savings to impress the Treasury. We have been told

that the savings may not go back to Treasury but be applied for

other priorities within the NPWS, if Treasury agrees.

This is not good enough - it leaves the NPWS resources and

priorities at the mercy of Treasury, and effectively negates the

Government's election promise. The NPWS cannot afford to lose ANY

funds, and any reordering of budget priorities has to be the

decision of the Minister for the Environment, Bob Debus, not a

bean counter in Treasury or in the Premier's Department.

The NPWS restructure is also being driven by a theoretical

model which will weaken the park management and nature

conservation arm of the Service. It strips support services from

districts and sub-districts and it seeks cost savings of

$3million a year from districts. It throws away the hardwon

community relations gains in rural areas over the past five years

from programs for pest animal and weed control, fire management

and neighbour relations, driven by district managers. District

managers, and their relations with rural communities, are to be

abolished for new, more remote regional managers in new `super

districts' whose job requires a focus on business development.

The research capacity of the NPWS may be handed over to State

Forests and other resource agencies.

NPA has protested, and will continue to protest, at these and

other potentially negative impacts of the restructure. We hope

that the Minister and the Director-General and their advisers are

listening.

Noel Plumb

Executive Officer

Walk against woodchips

Join a peaceful protest against the destruction of our native

forests!

Walk and bus from Sydney to Eden for a finale on 10 October at

the Daishowa woodchip mill. The walk begins on 2 October and you

can join us at the chip mill, or anywhere on the way as a

daywalker. For more information ring Margaret Barnes on 0414 489

035; or Therese Elliott on 9279 2855.

Biodvidersity Act conference The National

Environmental Defender's Office Network is holding a one-day

conference about the Environment Protection and Biodiversity

Conservation Act 1999. A major focus will be who can and ought to

regulate environmental matters. It will also look at whether the

Act reflects an appropriate division of powers between the

Commonwealth and States. The conference will be held in Sydney on

14 October. To find out more, ring the EDO on 02 9262 6989 or

e-mail edonsw@edo.org.au

Plant conservation The Australian Network for

Plant Conservation is holding its fourth national conference from

25-29 November in Albury. Its main aims will be to bring

information to conservation practitioners; to promote best

practice; and to form partnerships between community, industry

and government. Please contact Countrywide Conference Management,

ph 02 6040 1064 or see http://www.anbg.gov.au/anpc/4thconf.html

Mona Vale link threat

NPA has been concerned for many years to protect the bushland

corridor on Mona Vale Road ridge at Terrey Hills, near the St

Ives Showground. This ridge dominates much of northern Sydney and

is of immense landscape and aesthetic importance. It is also of

very high conservation value, as it includes bushland which

provides the only link between the Ku-ringgai Chase and Garigal

national parks. The link is critical for biodiversity and

provides a corridor for birds, bats, winged insects, pollen and

seed; in time, solutions will be found to provide wildlife access

under Mona Vale Road, which presently divides the land.

Unfortunately, this link - the best bush - is now to be sold

at auction by the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council. The

site is former Crown Land which was granted to the Land Council

under a land claim in 1988. The land is advertised as ideal for

plant nursery, hospital or residential units these and other

allowable uses would effectively destroy the bush.

I have addressed a community rally, called by the local MP, of

over 300 people opposed to the sale; and NPA has asked the

Minister for the Environment to acquire the land to protect it

from development. The Minister has agreed that the site has

regionally significant conservation values and has initiated

discussions with the Land Council for a land swap.

He has received requests from many individuals, conservation

groups and catchment committees to purchase the land.

Noel Plumb

Executive Officer

WANTED!

Nominations for Advisory Committee membership

will be invited by the NPWS around early October. We would like

to have the chance to endorse your nomination.

Please follow the procedures outlined in the item in "NPA

Matters" in the August Journal; or ring the NPA Office on 02

9233 4660.

News from the NPWS

Bridge to the past restored

Amidst the rugged sandstone cliffs near Gosford on the Central

Coast, the NPWS has joined with archaeologists and stonemasons to

reconstruct convict history along the Great North Road.

Under the NSW Government's Heritage Asset Management Program,

Clare's Bridge, the secondoldest sandstone bridge on the

Australian mainland, is being restored to its original glory.

Built in 1832 using convict labour, the bridge is a prime example

of the engineering feats undertaken by early roadbuilders in

their quest to push development from Sydney into the Hunter

Valley.

NPWS Central Coast Area Manager Tony Horwood said the works

are part of a commitment by NPWS to heritage preservation across

NSW. "Piecing together the history of the bridge and

determining the most appropriate reconstruction techniques is a

difficult process, but one which the entire team has been

relishing," Mr Horwood said.

The project involves the restoration of the southern abutment

of the bridge, which collapsed in the early 1960s. A number of

stone blocks missing from the original wall are being replaced

with sandstone hewn from local materials.

"Wherever possible, we have been ensuring that the

original material is retained and used in the reconstruction.

Authenticity is a very important issue in the conservation of the

bridge," Mr Horwood said. In keeping with its important

links to Australia's colonial past, Clare's Bridge is included on

the State Heritage Inventory.

More information about the Great North Road, of which Clare's

Bridge is a part, and adjoining Dharug National Park, can be

obtained from the NPWS Central Coast office on 02 4324 4911.

Liz Rossiter

Minister for the Environment

Having held the electorate of the Blue Mountains for 12 years,

I came to the environment portfolio in April this year with a

long-standing personal and professional interest in conservation.

Over the months since, I have gained a closer understanding of

the challenges of environmental management across NSW, as well as

the importance of an integrated approach if these challenges are

to be met.

Within the environment portfolio, the Minister has

responsibility for the Environment Protection Authority, the

National Parks and Wildlife Service, the Sydney Catchment

Authority, the Healthy Rivers Commission, the Zoos, Parks and

Trusts. Each of these agencies have played a role in the massive

environmental reform undertaken by the Carr Government over its

first term. This reform saw the introduction of a suite of new

legislative powers, as well as a 25 per cent increase in the

National Parks and Wildlife Service estate.

Ms Carmel Tebbutt has been appointed as Minister Assisting the

Minister for the Environment, with a broad range of

responsibilities incorporating the full range of the portfolio.

I see this term as a period of consultation, and a time to

tackle some of the harder, longer term problems that face our

community.

Although I have a broad interest in the environment, I would

like to see progress on two issues in particular: dryland

salinity, and greater protection for bioregions in western NSW.

Dryland salinity is a vital environmental issue that will

require long-term strategies to combat a problem created over

many years.

Responding to this problem means finding ways to tackle the

immediate impacts, as well as safeguarding against any future

damage.

The Government is already dealing with some of the issues

through its broader water reforms. Projects bringing together

government agencies, the community and industry are also being

undertaken, for example an Environment Protection Authority

program to control discharges of salinity to the Hunter River

from mines in the area.

The past four years have seen an increase in forest reserves

of 600,000 hectares on the North Coast and the Eden region. Over

the next four years, however, I will focus on achieving greater

protection in western NSW which, compared to eastern NSW, has

little land formally protected as national parks and reserves.

The NPWS is currently undertaking bioregion assessments, as part

of the NSW Biodiversity Strategy. Assessments already finished

reveal an environment rich in both natural and cultural heritage.

Bob Debus Minister for the Environment

Waterways - logging, boating & damming:

"We will meet them on the beaches ..."

Brian Everingham*

Relaxing beside the water within a national park is special,

treasured among the memories of many who enjoy nature and those

peaceful moments with friends and family. Fossicking around among

the rock pools, listening to the water whilst boiling up a brew,

or enjoying a glass. Watching the kids playing safely in the

shallows. Going for a long swim, just enjoying the peace and

quiet. Drowsing on the beach after a long walk.

Until recently, you could go to a number of estuaries, rivers

or lakes and at least pretend that you had escaped from the

pressures of industrial society. But these experiences are

undergoing a transformation, wrought largely by technologies that

were not envisaged when the rules governing national parks were

formed.

The commons we share within national parks include the

opportunities to escape from the presence of machines. Being able

to hear the lapping of the water, the call of the bird or the

symphony of the wind through the she-oaks is part of the magic.

So too is swimming in water without the taint of oil, and with no

need to look out for speed boats. Another facet is being in

harmony with the place, and knowing that those others who share

that place also share the values that make it so special.

Protecting these fragile commons from those who would carelessly

destroy them has been a driving force behind the powerful

opposition to machine activities like the use of trail bikes, or

4WD vehicles.

Drawbacks of boating What I am about to say

could be misinterpreted as criticising those who use boats. That

is not the case.

Far and away the majority of boat users who will be reading

this article share the same values and exhibit the same

environmental sensitivity as the majority of those who walk into

a national park, and leave only their footprints. But

machine-enabled access not only makes access easier (increasing

user numbers), it brings with it inherently non-natural

characteristics. It also is democratic, allowing the uncaring the

same ease of access as those who do care. And it empowers those

who do not care with far more power to do harm than they would

have under their own steam. The call I make is to face up to the

new challenges, not to victimise responsible boat users (who,

from my experience, express exactly the same concerns as I am

raising here).

So, that having been said, on with the discussion.

Parks with substantial bodies of water now face a new

challenge in the march of machine use, not from the land, but

from the water. In the much-loved Royal National Park, for

example, we now see this new pressure in issues like: Once quiet

areas such as Bonnie Vale, in the past mainly used by families

for picnics and swimming, are now for many weeks of the year

dominated by the sound and fury of jetskis whizzing across

Simpson's Bay, the operators often beaching them onto the sand of

the foreshore at speed. There have been serious incidents as a

result of this new hazard, and the previously safe swimming areas

are now less welcoming for those who are not confident enough to

brave the high-speed jetskis.

Seagrass beds, the nurseries for much of the valued

biodiversity of the waterways, are being physically challenged.

The Posidonia beds of the east coast are noted as being important

habitats, now in decline and not given to regrowth. Aerial

photographs show circles gouged out of these beds in the Hacking

River by anchor chains and moorings, as boat users seek to anchor

close to the shoreline of the Royal.

Groups of cruisers are now common in South West Arm, rafting

up for days and, as a side effect, discharging sewage through the

hull into a national park waterway. Even ignoring the contested

question of long-term impacts, few national park users would

expect to wade through sewage on the foreshores of the Royal,

particularly without any warning as to its presence.

The Basin is one of the truly magical places in the Royal.

Wetland habitat with a mixing of fresh and salt water. Birds of

all kinds and beautiful clear water.

Perfect for a quiet walk or some hours of birdwatching. That

is, at least, until the local jetski user or group in a `tinnie'

decide to have a look. Then see the birds scatter, flushed from

their nests by the noise. And then flushed again with the next

rush - all day. Then smell the oil in the water, and you have to

wonder how consistent this all is with the concept of respecting

nature, intrinsic to the concept of the national park.

These pressures of technology and numbers are being compounded

by the promotion of increased boating facilities within, or

adjacent to, national parks, without any comprehensive

consideration of the impacts or the management issues that ought

be considered. Again taking the Royal as an example, we can see

the next generation of problems being seeded by today's actions:

The beach at Jibbon is soon to see a substantial increase in

moorings put down by the NSW Waterways Authority, without

evaluation of the impacts on the park and the park values. Will

this add to these pressures? Should the promotion of boating

access be accompanied by other management actions to protect the

park values, or the amenity for non-boat users? Neither the NPWS,

nor Waterways, seem to be engaging in any careful consideration

of these issues.

Illegal moorings have been dropped into national park areas,

to facilitate cruisers rafting up. These having been removed, the

same boating interests are now using political pressure and legal

arguments to force NPWS to accede to their demands (at the same

time refusing to even consider a rule to prevent sewage from

boats being discharged into the waters of the Hacking).

A new boat ramp has been proposed for the Bonnie Vale picnic

area, over NPWS and NPA objections.

This argument is ongoing, with some boating interests seeking

to appropriate national park areas and scarce financial

resources.

I have illustrated all these issues with examples from the

Royal, because that is the national park that I know best. But I

also know from other areas that these are not isolated incidents.

I know that similar issues are emerging in most estuarine parks,

and in many inland parks where there are significant bodies of

water. There are many other issues that I could highlight - the

failure of the policing authorities to enforce existing rules;

the jurisdictional chaos that plagues the intersection between

land and water (and between NPWS, Department of Land and Water

Conservation, Fisheries, Waterways and local councils); the

disgraceful behaviour that is exhibited by a minority of boat

users.

But the point is, I think, made. New boating technologies and

growing user numbers are creating new challenges for national

parks, and new management solutions are needed before these

problems get totally out of hand.

The national park common that is being rapidly eroded is the

opportunity for peaceful, low-impact appreciation of the

waterways in a natural state. It encompasses not only the

biodiversity or aesthetic values of the national parks; it also

includes the values that the users of the parks generally share,

that place such importance on respect for nature and our land.

The importance of what could be lost if the waterways within

or on the boundaries of national parks remain abandoned to

water-based machines cannot be overvalued. If we want to be able

to offer the same special experiences to our children, we will

have to do something about it. The price of peace (even in

national parks) is always vigilance.

Policy and action So what needs to happen?

Minimally, the government has to take on a responsibility for

actually managing these issues, in some sort of integrated,

values-based way. To date, bureaucratic turf wars and a degree of

confusion have been more of a frustration than a threat to

national park waterways. But that time has now passed. If the

government does not take on the challenge then we who love

national parks will find the waterside experience in every major

national park waterway degraded and debased. Solutions are

possible, with relatively little effort, and indeed in line with

previous policy announcements of the NSW Government.

Regardless of whether the authority is Fisheries, or NPWS, or

some other agency, national park values need to encompass the

adjacent or enclosed waters, to protect those values. More marine

reserves are needed. A mistake we ought not to repeat is to

create reserves only for the untainted jewels of the waterway,

(viz. Marine and Estuarine Protected Areas under World

Conservation Union rules). We need management reserves as much to

protect the values of the terrestrial parks as to protect

biodiversity within the waters, and we should be willing to

create innovative solutions to these complex management problems.

We also need to be serious about how we deal with the

management issues that go with boating infrastructure on or near

national parks. Whilst such demands are no less (or more)

legitimate than the demands of other users of parks for improved

facilities, any such facilities should be considered only within

well-developed management frameworks that reduce the erosion of

the commons. Such management plans will have to be negotiated

with boating and fishery authorities and with clear compliance

requirements and measures of effectiveness. Without this,

improved facilities will only lead to erosion of park values.

Finally, strong enforcement of noise, safety and pollution

controls on the waterways is essential. It is not only NPWS that

is under-resourced for its role. It is relatively easy for other

policing authorities (notably Waterways) to redirect their scarce

resources away from protecting park values, towards other more

pressing needs.

None of this change will happen, of course, without the users

of the national parks making their needs powerfully felt in the

corridors of power. There is apparently some rethinking of some

of the issues raised in this article going on within some

government agencies, largely as a result of changes in ministers

after the NSW election. Sadly, the impact of waterway issues on

national park values is not one of the agenda items.

Perhaps it is time that the members of NPA made it clear that

it ought to be?

* Brian Everingham is NPA Secretary.

OCTOBER 1999 11

Durras:

enduring heart

Geoffrey Bartram*

I t's a rare month on the South Coast of NSW when the media do

not present us with yet another report of a wetland in crisis -

"Lake crisis: call for dredging", "Fish die in

Kianga Lake", "Bird's paradise today, 3,000-home

subdivision tomorrow", and so it goes, on and on and on.

Wetland is a general term for swamps, billabongs, lakes,

saltmarshes, mudflats and mangroves, simply areas that have

acquired special characteristics from being wet on a regular or

semi-regular basis. Since the arrival of Europeans we have dug

up, filled in, drained, interfered with, poured, seeped and

dumped into our wetlands such a vast range and quantity of

pollutants that many have given up the fight for survival.

Finally we are being forced to wallow in and eat the results of

our ignorance, greed and short sightedness.

Unfortunately the poor management of wetlands has been

widespread and in some regions the results of ecological

breakdown far more newsworthy and devastating than anything so

far experienced on the South Coast. The recent Wallis Lake

incident - where one died and many were hospitalised from eating

shellfish marinated in sewage - has frightened local councils

into action, knowing they may be liable for allowing known

polluting processes to continue.

One lake on the South Coast, Durras Lake, just north of

Batemans Bay, has for the most part escaped the ravages of

development. Most of its catchment is undeveloped and forested.

Once Durras Lake would have been nothing special, just one of the

hundreds of pristine lakes and lagoons that dotted the NSW coast.

But today it is regarded as the best of its kind in the State, a

glimpse of what a large coastal waterway would have looked like

before the arrival of Europeans. The NSW Environment Protection

Agency (EPA) has chosen Durras Lake as the site of a major new

study to understand what a near-pristine coastal waterway is

like. The findings of this study will allow the EPA to give

advice on how developments near other coastal wetlands will

affect them.

An ever changing environment Durras Lake is a permanent,

intermittently opening and closing, barrier, estuarine lake. That

mouthful refers to one of the special characteristics of Durras

Lake: that it is formed behind a barrier of sand dunes which at

times completely cut the lake off from the sea. At other times,

the barrier is breached by a combination of big seas and tides

and high freshwater input from the catchment. Then the tide flows

in and out until the sand barrier re-builds and cuts the lake off

from the sea once more.

Estuarine flora and fauna are, by necessity, remarkably

adaptable to these ever changing environmental conditions.

Salinity and water-level fluctuations vary dramatically. For some

fish, the salinity level in the lake is too high for breeding.

They head up into the freshwater creeks when the time comes for

them to spawn and return to the saline lake to grow and develop.

Flora are also affected by changing conditions of salinity and

fluctuating water levels. At times the Casuarina glauca which

line the shore have their feet in saline water, while for other

prolonged periods they are left high and dry. Similarly the

saltmarsh communities are at times inundated, then left

uncovered, exposed to the sun and wind. These natural processes

have been going on for centuries.

It is the recent `unnatural' inputs which have had devastating

impacts on our wetlands. These include development for housing or

farming, which inevitably result in higher than normal nutrient

and heavy-metal levels from runoff, sewage and fertiliser and

consequent changes to aquatic vegetation. Vegetation clearing,

logging and roadworks often allow large quantities of sediment to

be carried into wetlands, smothering aquatic vegetation and

increasing turbidity. Increased sedimentation has been the demise

of seagrass beds throughout NSW. Many major estuaries have lost

up to 80% of their seagrass beds in the past 30-40 years. Lake

Macquarie, for example, has lost 44% of its seagrass, the

Clarence River 90%, due to increased turbidity and a general

decline in water quality.

Durras Lake faces significant threats. In 1985, 504 hectares

along 5 kilometres of the Durras Lake shore was rezoned for urban

development. The Durras community saw the threat that was posed

to Durras Lake and the Friends of Durras (FOD) was formed, aiming

to buy the designated development block. Despite a $1 million

price tag, FOD were persistent lobbyists and fundraisers until in

1993 they presented the NSW Government with $113,000. The land

was bought and added to Murramarang National Park, but other

development pressures must be constantly resisted.

The other major threat is from logging of the catchment, 76%

of which is managed by State Forests. The native forest logging

industry has a clear agenda to intensify logging , and State

Forests is under pressure to supply woodchips from the south

coast to the Eden mill. FOD has severely constrained logging

operations around Durras Lake in recent years, demanding that the

catchment be protected. State Forests does not even properly

manage its abandoned, eroding forestry roads, which carry

sediment to the lake.

When ignorance is not bliss One of the major factors that has

threatened lakes and wetlands is ignorance. Ignorance of the

benefits a wetland has when managed in its natural state, and

ignorance of what environmental disasters may take place once a

wetland is removed or badly degraded.

Estuarine wetlands are recognised as the productive engines

that drive inshore fishing. Some two-thirds of commercially and

recreationally valuable fish spend at least some part of their

lifecycle in an estuary. The fishing and tourism industry, indeed

the whole community, are paying the price of poor management and

so too is the economy.

We are learning; but even despite the hard evidence of

scientific studies and in-your-face disasters like Wallis Lake,

we continue, too often, to learn the hard way. We can no longer

use ignorance as an excuse. There is a wealth of information upon

which to make good management decisions and put an end to the

ignorant mistakes of the past.

Durras Lake is the heart of the Greater Murramarang National

Park, one of the wonderland forest areas of the south coast. This

proposal - to create an expanded Murramarang National Park has

been presented to Premier Carr by FOD and NPA (Milton Branch).

His Government will decide by the end of this year whether to

protect the Durras Lake catchment or continue to allow it to be

logged. The choices appear clear cut apply the precautionary

principle and ensure that future generations will be able to

enjoy, as we have, Durras Lake and the fruits it delivers; or

continue logging for small economic gain and run the real risk of

turning yet another pristine wetland into an unproductive

quagmire, a bottomless wet hole into which endless rehabilitation

money will need to be thrown.

Act Now!

You can help those who may find this decision difficult to

make by writing to: The Hon Bob Carr, Premier of NSW, Parliament

House, Sydney 2000 asking him to protect Durras Lake and its

catchment by creating the Greater Murramarang National Park. The

park proposal is on-line at: http://www.morning.com.au/go/fod/

For further information please contact Geoffrey Bartram, phone 02

6281 6434 or email: geoffreybartram@hotmail.com.

* Geoffrey Bartram is a NPA member; co-ordinator of the

Friends of Durras; and a conservation representative on the

Environment and Heritage Committee for the Southern Regional

Forest Assessment.

JOHN PENKINS Canoeist on Durras Lake PHOTO NO 3 CROP AS MARKED

REDUCE BY 22% PHOTO NO 4 EXPAND TO 255% Pelican on Durras Lake

GEOFFREY BARTRAM 12 OCTOBER 1999

PHOTO NO 5 CROP AS MARKED SAME SIZE Spotted gum/burrawang

forest, typical of the Durras Lake catchment GEOFFREY BARTRAM

OCTOBER 1999 13

Damming

the planet

Stuart Blanch*

H umanity's dominance over the world's large rivers is a very

recent thing. Hoover Dam on the Colorado ushered in the era of

big dams in 1936. In the three-score years and three since, over

40,000 large dams have been thrown up across - almost without

exception - every major river in the world. That's one every 14

hours. China has about half of the world's large dams, the USA

about 5500, the CIS about 3000, Japan 2300 and India 1100.

Australia has 409.

Russian writer Maxim Gorky said dams `make rivers sane'. The

environmental, social and economic impacts of flow regulation in

the past half century, however, show that the pursuit of bigger

and bigger dams by engineering focused bureaucracies and

construction companies has been insane.

Reservoirs worldwide have submerged over 400,000 square

kilometres, or six Tasmanias, of river valleys and their diverse

ecosystems. Many rivers are little more than staircases of lakes

now, and completely unsuitable for many riverine species.

Fisheries biologists have a rule of thumb that fish biodiversity

in dammed tropical rivers is only 20-40% of that of the

free-flowing river.

The 130 or so dams in the Columbia River Basin (USA) have

decimated runs of wild salmon, with numbers plummeting from 10-16

million to under 1 million each year; from 1960-1980, the cost to

fisheries is estimated at US$6.5 billion. Diverting flow for

irrigation from the highly controversial Sardar Sarovar Dam on

the Narmada River in India is predicted to decimate the

healthiest fishery left in India. Similarly, the partially built

Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze, which will be the world's

largest dam if completed, is likely to be the nail in the coffin

for the last couple of hundred endangered Yangtze River dolphins.

Dams are not the only means of regulating rivers.

The Pantanal in south-west Brazil, the world's largest

wetlands, will shrink if the infamous Hydrovia River

channelisation project is completed. Straightening bends of the

Parana and Paraguay rivers, and blasting rocks to permit passage

of ocean-going ships, will reduce the duration of flooding of

this magnificent savanah woodland, increase channel erosion and

produce more destructive floods downstream. The Pantanal - home

to many threatened species such as the giant otter, jaguar and

beautiful hyacinth macaw is predicted to constrict by at least

10%.

Wherever rivers cross national boundaries conflicts over water

sharing arise, with the environment often overlooked. Floods that

eighty years ago fed the Colorado delta wilderness in Mexico now

water lawns in Las Vegas and cotton in the desert.

The Kavango River descends from the Angolan Highlands,

traverses semi-arid Namibia and throws its floodwaters out across

the dry Kalahari in Botswana, forming the `Last Eden of Africa',

the Okavango Delta.

Namibia plans to pipe 20-120 million cubic metres of water

from the Kavango, just before it crosses into Botswana, to its

capital Windhoek 250 km away. As with the Colorado, diversions of

such magnitude would significantly reduce wetland area and impact

upon the Delta's magnificent wildlife, particularly in dry years

when the Namibians would want the water most.

Turkey's South East Anatolia Project plans scores of dams on

the Euphrates and Tigris rivers for hydropower and irrigation,

the biggest of which is the Ilisu Dam 65 km upstream of the

Syrian and Iraq border. Even without Ilisu, the three countries

collectively lay claim to 55% and 12% more than average annual

flows in the rivers, respectively. If completed, Ilisu will take

one and a half years to fill and be able to stop all flows to the

downstream countries for several months. Sedimentation will be

rapid - the dam's life expectancy is just 80-100 years.

How is it that in less than a person's lifetime an ecological

disaster of such global proportions could have been perpetrated

on the very rivers that sustain our existence? By sacrificing

commonsense in the pursuit of engineering solutions and ignoring

ecological advice, the long-term impacts of river regulation have

been ignored.

Anti-dam campaigns throughout the world in the last two

decades have made governments seek ecologically benign ways of

harvesting water and supplying hydropower. The World Commission

on Dams, a joint attempt by pro- and anti-dam interests to

resolve dam conflicts, has the backing of such disparate groups

as the World Bank, World Wide Fund for Nature, the World

Conservation Union (IUCN) and dam builders.

Dams are also starting to come down - about a dozen in the US

and a couple in France so far, mainly to restore endangered

salmon fisheries and protect indigenous fishing rights.

Socio-economic analyses showed it was cheaper to remove some of

these structures than to maintain them, a highly ironic outcome

given the economic rationalist paradigm that prevailed when such

dams were built.

By the same argument, the time for carefully considering the

removal of weirs and dams in the highly degraded Murray-Darling

Basin has arrived.

Over 15m high.

* Dr Stuart Blanch is Coordinator of the Inland Rivers Network

(ph 02 9241 6267, e-mail sblanch@irnnsw.org.au).

IRN is a network of conservation groups and individuals,

including NPA, with a focus on inland rivers and wetlands of NSW.

14 OCTOBER 1999

It's

time!

to stop peat mining

Phillip Kodela*

The long-term benefits of protecting peatlands outweigh the

short-term monetary gains acquired for peat products and the

possible costs from damage associated with the depletion of the

limited peat resource.

W hen you consider (1) the significant conservation values of

peatlands, (2) the destructive environmental impacts of peat

mining, and (3) that there are horticultural alternatives to

peat, it begs the question: why does peat mining still occur? The

economic arguments for mining peat are shaky, especially if

indirect costs and loss or damage to nonconsumptive values are

factored into the equation of real costs. And in the worst cases,

the result of mining may involve environmental losses and costs

to the government, ratepayers and broader community that far

exceed any financial benefits that were gained by a relative few.

Wingecarribee Swamp is a prime example of where maintaining

the natural values would have been more prudent in the longer

term than the enormous costs now associated with environmental

damage, water pollution and rehabilitation resulting from peat

mining (see, for example, August NPJ).

And what of the heritage values on which we cannot place a

price?

When will the rhetoric of `ecologically sustainable

development' be effectively adopted and practised for the wise

use of resources, environmental protection and better longer term

economics?

An abbreviated case against peat mining, starting locally:

Peatlands are rare in Australia.

Peatlands provide important natural functions in catchments.

The peatland ecosystem provides habitat for distinctive flora

and fauna (including rare and unusual species and communities),

and performs biological, chemical and physical processes. The

ecological and hydrological functions of a peatland help maintain

catchment stability and water quality through water regulation

and filtration processes.

Peat deposits are an archive of environmental history. Each

site contains a unique scientific record of past vegetation,

climate and environmental processes. The study of past vegetation

and climate provides insights into vegetation and plant dynamics,

behaviour and responses to change that may help with

understanding existing communities and their management.

Peat mining directly affects a living, dynamic wetland

ecosystem where the peat/sediments, hydrology and biota are

interconnected.

Interfering in any of these components can disrupt other parts

of the system. For example, peat extraction causes hydrological

changes, such as alterations in water-table levels, that affect

ecological and biochemical processes in the wetland. The impacts

of peat mining will not be restricted to the local or immediate

area where the peat is being extracted, but will be felt in other

parts of the wetland, with potential impacts in the broader

catchment.

The long-term benefits of protecting peatlands need to be

measured against the short-term gains of peat mining. It is often

economically beneficial to maintain peatlands as naturally

functioning wetlands in catchments, especially when environmental

costs of mining are factored into the analyses.

The costs to rehabilitate or restore areas damaged by peat

extraction may be greater than the short-term economic gains from

mining peat. Peat mining can cause long-term or permanent

environmental damage and losses (such as impacts on water

quality), and greater monetary costs to repair damaged ecosystems

and catchments. Threats to biodiversity, rare species and other

heritage values must be considered.

The NSW Wetlands Management Policy (1996, page 5) states that

the Government will adopt a common goal to guide decision making

for wetlands: "The ecologically sustainable use, management

and conservation of wetlands in NSW for the benefit of present

and future generations". Peat mining is in direct conflict

with this goal. It is not an ecologically sustainable industry;

peat is effectively a nonrenewable resource (the rate of

extraction far exceeds the renewal capacity of the resource at

mining sites, that is if there is any natural regeneration of the

peat after mining has altered and disrupted the ecosystem).

Exploitation may well go beyond the tolerance of the natural

peatland system.

There is often inadequate knowledge about peatland habitats

and the possible impacts of peat extraction. The assessment of

mining proposals should take into account the precautionary

principle.

There are now well-established alternatives to peat for all

its horticultural uses. Using peat alternatives recycled from

waste or byproducts can contribute to reducing waste disposal and

pollution problems, as well as promote new green industries and

associated economic benefits. You can help by using peat-free

products in your garden, and informing your plant nursery and

friends.

* Dr Phillip Kodela has investigated peatlands in various

research and management projects.

OCTOBER 1999 15

Mining

Negotiating the pitfalls

Anne Reeves*

D evastating impacts of mining on the environment and on local

people have been documented worldwide. Whilst it is true that

mining only disturbs a small fraction of the world's surface, it

is also true that when its impact is upon certain critical points

of the environment, the outcome can be catastrophic; these

critical points often also involve the surface and subsurface

hydrology of the area.

The Big Australian, BHP, has finally admitted liability for

some of the disastrous consequences of the Ok Tedi Mine in New

Guinea, where pollution of the Fly River has resulted in

widespread damage to the river environment on which the local

people depend. Among the groups highlighting the international

concerns are the Bondibased Minerals Policy Institute, as well as

Friends of the Earth (FoE) internationally along with many

nationally based FoE groups.

Closer to home, the collapse of the ecologically significant

Wingecarribee Swamp near Robertson during a flood was due to the

zone of weakness created by peat mining, according to the three

hydrology consultants who examined it. Acknowledged as a wetland

of outstanding significance, it has featured in past National

Park Journals and there is coverage on peat mining in this same

edition (see opposite page). A year after the catastrophe, far

too little has been achieved in the way of rehabilitation; and

the successful court action brought by the Environment Protection

Agency, against pollution from the mine prior to the collapse,

leaves little chance of the $217,000 fine and $90,000 costs being

paid - the company involved, Emerald Peat, has gone into

voluntary liquidation. The question of Sydney Water's cleanup

costs was stood over.

Over the years, this Journal has carried many references to

the potential and actual adverse effects of mining ventures on

natural areas. Within NSW alone these include: mineral-sand

mining and its legacy of bitou bush as a dune coloniser;

construction-sand extraction off Royal National Park; limestone

from Colong Caves and at Yessabah; gold from Lake Cowal and

Timbarra; long-wall coal mining in the Gardens of Stone and at

Cataract.

Not all proposals have gone ahead. In some instances cost/

benefit analysis and/or public protest have led companies to

withdraw. In other cases legal challenges have resulted in

refusal, extensive modification to reduce impact, and even

amendments to law and government policy. In WA, the Denmark

Environment Centre had to go all the way to the Supreme Court to

confirm their right to even be heard before their Mining Warden

over sand-mining proposals in an excised portion of

D'Entrecasteaux NP; while in SA there is the very imminent threat

of legislation to allow mining in Yumbarra Conservation Park.

The mining industry is sensitive to public pressure, however,

and has been active in the last few years in seeking to improve

its image and practices. Perhaps led by the coal industry in the

Hunter Region - where there has been strong and well-connected

concern over the impacts on neighbours and their livelihood from

the proliferating open-cut mines - there have been commendable

moves to lift the game, for instance through promulgation of best

practice and a code of ethics. However, implementation is

voluntary, and dependent on peer and consumer pressure.

At Lake Cowal, approval for North's deep open-cut gold mine

intruding into a section of the lake came after a second

Commission of Inquiry was conducted to evaluate a revised

proposal with lesser cyanide levels; power lines relocated away

from bird flight paths; and other modifications. The initial

development application was rejected as unacceptable by Premier

Carr in a decision announced during the 1996 Brisbane Ramsar

Convention meeting, fulfilling a promise to Milo Dunphy shortly

before his death (see also NPJ August 1999).

In this, as in so many other ventures, the influential drivers

for mine approval were the potential profits for the company

itself and those who wanted to boost a local economy in decline.

However, lateral thinkers in the company, the unions and the

environment movement proposed exploring the possibility for

common ground should the mine get the go-ahead.

This led to the adoption of a Memorandum of Understanding (NPA

is one of the signatories) to establish an Environmental Trust,

aimed at improving conservation management and protection of

significant wetland values. This move is probably a first,

reflecting a generational change of approach from the mining

industry, and could serve as a pilot.

While no compensation for loss of wetland integrity, it

nevertheless is intended to ensure some of the mining profits

contribute to longterm environmental benefits alongside the

economic ones. These include protection of important remaining

wetland values, native vegetation and associated natural and

Aboriginal heritage values around Lake Cowal; and potentially to

help offset the threats of salinity, due to past clearing and

changed water regimes associated with irrigation and dryland

farming.

Many will be watching to see whether the hoped-for outcomes

will be achieved over time as people, and possibly even mine

ownership, change.

"Diversification" is the buzz word for those seeking

to provide new and alternative incomes in regions of economic

decline, and to most governments, local and State, a new mining

proposal inevitably appeals. However, the short-term injection of

new money and jobs carries a price tag. Infrastructure

assistance, tax holidays and facilitated access to ancilliary

approvals turn sour when the venture collapses, is mothballed or

comes to an end. Employees and creditors may be left high and

dry; and the ecology disrupted, with remote and protected areas

forever changed, including by the expensive legacy of leachate

pollution and subsidence. The Department of Mineral Resources has

lifted its requirements concerning cradle-to-grave management

planning requirements and bonds, but these require policing and

may be insufficient to counteract unexpected outcomes.

Furthermore, it is not the mine alone that affects the

environment: there may be the impacts of prospecting; of roads,

powerlines and so on; perhaps newcomers into the region; the

support services; the pets and recreational activities - all

contribute to change.

All of us in the modern world are dependent to a greater or

lesser extent on the products of mining. As resource demands

increase along with human populations, there is ever greater

pressure on our natural world and our precious protected areas.

Reconciliation of protecting biological systems and natural

heritage with demands for use is increasingly urgent. The World

Commission on Protected Areas, one of several international

commissions that operate under the wing of IUCN (the

International Union for the Conservation of Nature, now the World

Conservation Union) has developed a Position Statement on Mining

(see box), now formally noted as such by the WCU-IUCN Council in

April 1999.

Since individual countries need to adapt these principles to

local circumstances, it would be timely for the NSW Government to

review mining legislation as a first step in tandem with careful

review of the appropriateness of IUCN categories - with a view to

ensuring better biodiversity conservation, rather than

backsliding into multiple use at the expense of habitat integrity

and ecosystem viability. NPA has already been involved in moving

towards this, working with the Environmental Defender's Office to

develop an extensive paper on the matter; meeting with decision

makers; and assisting the Nature Conservation Council to develop

policy as guidance for environment groups throughout the State.

* Anne Reeves is Vice President, and NPA's Lake Cowal MOU

representative.

Extract from WCPA Position Statement Introduction This

position statement is put forward as a global framework statement

which recognises that clear rules are easier to understand and

defend than ones which depend too much on interpretation. This

position statement acknowledged the increasing application of

"best practices" environmental approaches and lower

impact technology within the mining industry as well as examples

of support for conservation activities.

However, WCPA also notes that exploration and extraction of

mineral resources can have serious long-term consequences on the

environment. The guiding principle adopted in this statement is

that any activity within a protected area has to be compatible

with the overall objectives of the protected area.

[Point] 2. Exploration and extraction of mineral resources are

incompatible with the purposes of protected areas corresponding

to IUCN Protected Area Management Categories I to IV, and should

therefore be prohibited by law or other effective means.

3. In Categories V and VI, exploration and minimal and

localised extraction is acceptable only where this is compatible

with the objectives of the protected area and then only after the

assessment of environmental impact (EIA) and subject to strict

operating, monitoring and after-use restoration conditions. This

should apply "best practices" environmental approaches.

5. Proposed changes to the boundaries of protected areas, or

to their categorisation, to allow operations for the exploration

or extraction of mineral resources should be subject to

procedures at least as rigorous as those involved in the

establishment of the protected area in the first place. There

should also be an assessment of the impact of the proposed change

on the ability to meet the objectives of the protected area.

7.In recognising the important contribution the mining

industry can play, opportunities for co-operation and partnership

between the mining industry and protected area agencies should be

strongly encouraged.

Collaboration with the mining industry should focus on

securing respect and support for this position statement;

broadening the application of best environmental practice for

mining activity; and exploring areas of mutual benefit.

[The full text of the seven-point statement and this

introduction is available from the NPA Office.]

OCTOBER 1999 17

Koongarra - Kakadu's sword of Damocles

Allan Fox*

T he map of Kakadu in the 1998 Visitor Guide shows three

mineral areas in white. One, Ranger, has been mined for twenty

years; Jabiluka has just got the green light; while the third,

Koongarra, sits too quietly along the south side of Nourlangie

Rock and Mount Brockman. This mineral lease is standing like a

time bomb ready to be activated as soon as the present government

feels the urge. Kakadu is an Endangered World Heritage Area while

ever this situation exists.

Some history Opening of the Ranger Mine with its three massive

pits was given the go-ahead by one of a package of four Federal

Bills as a result of the Ranger Uranium Environmental Inquiry

(the Fox Report) in 1979 which: (a) returned certain lands to

Aboriginal ownership; (b) established Stage 1 of Kakadu National

Park excluding the three mining areas; (c) permitted the opening

of Ranger mining operations; (d) established the Office of the

Supervising Scientist (OSS) to monitor and regulate the

"safe" operation of the Ranger uranium mining project.

The laboratory and functional centre of the OSS was

established at Jabiru adjacent to the mine, a location crucial to

a close supervisory function. It is now reported that this office

and laboratory is to be removed to Darwin, 250 km away, where it

can undertake other works in addition to its extra role of

supervising Jabiluka.

As for Jabiluka, the recent story of its controversial

approval is fairly well known. What is not generally known is

that during research for the book Kakadu Man, it was discovered

that the Jabiluka Environmental Impact Assessment was severely

flawed with regard to its record of Aboriginal sites of

significance within the mining area.

Pancontinental was warned that it would need to correct this.

Subsequently, the three authors received numerous phoned death

threats; Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service (ANPWS)

officers were intimidated and others severely compromised; the

Aboriginal Ranger Training Officer was threatened with dismissal,

and there was a threat of an injunction on the Service to keep

him out of the park on the trumped-up excuse that he was

`training Aborigines to dislike mining'; Service officers were

'used' in a conspiracy to destroy the credibility of one of the

authors. These activities and more were industry generated

(Energy Resources of Australia were not then involved with

Jabiluka) and involved the most senior levels of ANPWS, a

Brisbane QC, The Northern Land Council and of course the mining

company. Some of this incredible story was reported by Aboriginal

Affairs Minister, Clyde Holding, in his Second Reading speech to

the Amendments to the NT Land Rights Act 1984 (see Hansard).

It is clear from the incentives behind these activities of the

industry, the political chicanery and deceit - which ultimately

saw the approval given to the Jabiluka mine as well as the loss

of the UNESCO declaration of Kakadu as an Endangered World

Heritage Area by the current Commonwealth Government - that

cancellation of the Koongarra Project must be given top priority

by those interested in maintaining the integrity of what is

perhaps Kakadu's core park area, Nourlangie Rock and Mount

Brockman.

Why be concerned?

Unlike the other two mines which lie on the very important

though marginal Magela catchment, Koongarra lies on the

mid-headwaters of Nourlangie Creek which is a major tributary of

the South Alligator River, the central catchment of Kakadu. Any

outbreak of tailings would seriously affect critical wetlands as

well as the primary visitor area identified as that as far back

as 1969. As the proposal is for the Koongarra Project to refine

its own yellow cake on site, and to import reagents and to

produce large amounts of acidic tailings to be held in a dammed

valley, the Fox Report concluded: `seepage from this dam would

probably also be acid, with a correspondingly high concentration

of dissolved heavy metals. Thus any pollution from operations at

Koongarra would be a potential threat to the very valuable

wildlife of the Woolwonga Reserve. (Lower Nourlangie Creek area.)

The proposal to build the tailings dam in a natural drainage

system gives further grounds for concern, since it means that,

over the long term, as the protective works deteriorated, the

tailings would probably be subject to erosion'.

A heavy-duty road would be required to carry the thousands of

tons of sulphuric acid, pyrolusite, lime and ammonia to the site

from Darwin, while massive movements of ore would be removed from

the open pit to the mill. Disturbance to public areas at

Nourlangie and the stunningly beautiful and peaceful Gubara

(Saratoga Dreaming site) rainforest, springs and pond area would

be cataclysmic.

The Nourlangie Rock end of the project area is a place of

exquisite beauty with many acres of intricately etched sandstone

and geologically worked faults, fractures and joints, some faces

filled with huge quartz crystal deposits, standing over a maze of

gullies with clear green pools edged with rock ferns and meadows

of golden bladderworts in the deep shade of ancient Allosyncarpia

ternata.

The southern side of the outlier escarpment is an extremely

important Aboriginal area with numerous burial sites and places

of significance. As many nearby Aboriginal art sites and

occupation areas have been provided by the local ARTWORK NO 1

CROP AS MARKED SAME SIZE Location of Koongarra Source: ANPWS

Visitor Guide to Kakadu people for public interpretation, it is

essential that these other important sites along the Koongarra

Fault are preserved for the traditional owners' traditional

purposes.

Mining has no place in these environments of much higher human

and natural value. We must all speak up now for this wonderful

area and shut down forever the opening of the Koongarra Project,

and save economic rationalist governments from themselves.

Don't let us be beaten by timing and government chicanery as

was the case with Jabiluka.

References:

- Fox, R.W., G.G. Kelleher & C.B. Kerr (1977) Ranger

Uranium Environmental Inquiry. Second Report.

- AGPS, Canberra.

- Neidjie,W., S. Davis & A. Fox (1985) Kakadu Man -

Bill Neidjie.

- Mybrood PC, Queanbeyan.

* Allan Fox is a long-term member of NPA and for many years

kept an early version of the National Parks Journal alive. He was