River regulation salinity

Paul Lloyd

Project Officer

NSW Murray Wetlands Working Group Inc.

|

River regulation salinity

Paul Lloyd |

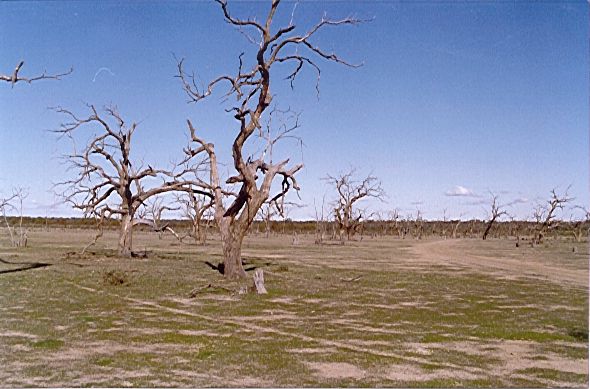

Dying black box across the bed of

Gol Gol Swamp

Photo: Paul Lloyd

Salinity is one of the largest long-term problems facing many parts of Australia. It is degrading and will continue to degrade our natural environment and our agricultural productivity. In most cases, it is caused by an increase in the amount of surface water seeping down to the water table; this effectively fills up the water table, bringing salty groundwater closer to the surface. This salt originally comes from very old marine sediments which were laid down millions of years ago when much of the area now comprising the south-west section of the Murray Darling Basin was a sea.

Dryland and irrigation salinity are well known, and their causes and potential long-term impacts are being increasingly appreciated. However, along the Murray River there is a third type of salinity river regulation salinity that many people are not aware of. While irrigation salinity is due to more surface water being held on the land, river regulation salinity is caused by more water being held in the river itself.

The Murray River is the most heavily regulated major river in Australia. Numerous structures, including large dams in its headwaters and weirs along its length, have altered the rivers natural flow patterns to provide water supply for regional development. Weirs raise the river level to allow water to be supplied for uses such as town-water supply and irrigation. However, the increased depth and weight of water in weir pools causes greater seepage into the groundwater. Over time, this increased seepage causes the groundwater under the weir pool to rise, bringing saline water closer to the surface.

Salinisation in the floodplain

Salinisation in the floodplain

Groundwater mounds have formed around most of the weir pools downstream of Swan Hill, and many of these are still expanding underneath the floodplain. Some floodplain areas adjacent to these weir pools are already showing signs of scalding and vegetation decline due to the shallow saline water tables. Usually the first areas to be affected are wetlands the lowest points in the floodplain landscape and therefore the areas closest to a rising watertable.

Several groups are working to rehabilitate wetlands along the Murray Floodplain in NSW, Victoria and South Australia. We can restore many of the natural values of these wetlands by re-establishing a natural seasonal drying phase or by reflooding a wetland that has been blocked off from the river. However, the effectiveness of such rehabilitation work now has to be weighed against the long-term risk of salinisation.

At Gol Gol Lake and Swamp near Mildura, a local community group has been working for five years to rehabilitate the wetlands. Their work has shown the nearby Mildura Weir pool is causing the gradual salinisation of the wetlands and the decline of the black box and lignum on the fringe of the swamp. The groundwater almost as salty as sea water is within two metres of the bed of the swamp. That is close enough to be drawn closer to the surface each time the wetland is flooded. The group now faces a dilemma: flooding the wetlands will hasten their decline. For the time being, the group has decided to keep floods out of the wetlands to avoid exacerbating the salt problem. The long-term health of the wetlands is still hanging by a thread.

Are there any answers?

Are there any answers?

As with the more well-known forms of salinity, there are no quick and easy solutions. The processes causing salinity have taken many decades to develop; actions to counteract them may need a similar timeframe to take effect. Regional salinity problems are often caused by broad-scale land and water management practices. These practices will only change if we find ways to minimise the disruptions and costs of that change. Upcoming studies will focus on more sophisticated ways of managing river flows and manipulating weir pool levels, initially to minimise seepage and then to lower groundwater levels. And this must all fit within broad-scale environmental flow management.

Paul Lloyd is a Project Officer with the NSW Murray Wetlands Working Group Inc.

|

|

National

Parks Association - Home Page |

|